- Malware Evolution

- Malware for non Win32 platforms

- Internet Attacks

- Malicious programs for mobile devices

- Spam Report

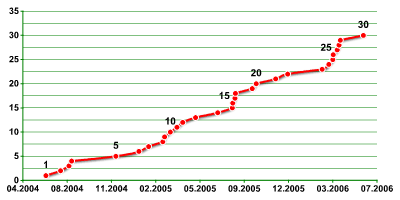

New mobile malware dynamics

At the beginning of 2006, writers of malicious code for mobile devices showed increased activity. They released a whole range of new malicious programs for mobile phones. These programs were notable for the variety of platforms that they targeted and for their expansion into a previously little explored area — that of mobile technologies. By February – March, the number of malicious programs for mobile devices was increasing at an average rate of 5 – 7 per week, and sometimes rising to 10. The year started with approximately 150 samples of all known viruses for Symbian, and by summer, the number had risen to almost 300. This was noted by most antivirus companies in their reports; however, it was difficult to establish the exact number due to the fact that different antivirus solutions detected the same program in different ways.

During the second quarter of 2006, the number of new samples stopped increasing. This applied both to known families, and to new malicious programs.

|

Virus writers continued to work on honing their knowledge and skills. They put particular effort into combating antivirus programs and investigating the possibility of infecting PCs via mobile phones. In this last case, they succeeded – the Cardtrap Trojan installs a range of Trojans for PCs to the phone’s memory card.

As regards already known viruses, over the past six months Comwar (a worm which spreads via MMS) became the most common malicious program in MMS traffic. Cabir, on the other hand, has demonstrated slower infection rates: we had received regular reports about Cabir infections in the winter, whereas by July we were receiving none.

Theoretical developments during the first half of 2006

For Symbian

Symbian malware has reached the stage where it is being developed for profit – we saw the first Trojan-spy for Symbian in April. Flexispy was being sold by its creator for 50 USD. The Trojan established full control over smartphones, sending information about the user’s calls and SMS messages to the malefactor.

For Windows Mobile

Windows Mobile, currently the second most popular platform for smartphones, also attracted the attention of malware writers. Known malware for Windows Mobile doubled during this period. This sounds more serious than it actually is given that there were only two examples of malware for Windows Mobile – Duts and Brador. However, these two new malware samples are undoubtedly proof of concept versions that could spark off new directions for the work of other malware writers.

Crossplatform malware

The Cxover virus is the first example of a cross-platform virus for mobile devices. Cxover begins by checking which operating system is working on the infected device. If launched on a PC, the virus searches for mobile devices accessible via ActiveSync. Cxover then copies itself via ActiveSync onto all accessible mobile devices. Once the virus is on a mobile device it attempts to copy itself onto accessible PCs. In addition, it deletes user files on infected devices.

The Letum worm, which was detected in April, continued the cross platform trend. The author exploited .NET; a programming environment that is suitable both for PCs and Windows based mobile devices. Letum is a typical email worm in that it spreads as an infected attachment and sends copies of itself to all the addresses in the local address book. Thus the boundary between stationery and mobile devices is demolished further. Now such devices can infect each other, and this is precisely an area that will cause serious concern in the future.

Although smartphones continue to be the main focus of criminal activity, regular mobile phones are also becoming a target for virus writers. During this period, the first malware for regular mobile phones appeared which used the J2ME platform to execute certain applications.

Another illusion was shattered: up to this time, most people had thought that it was impossible to attack regular phones. In fact, Trojan-SMS.J2ME.RedBrowser.a had probably already existed in the wild for some time and had even found some victims. A second variant followed the discovery of the first one.

The discovery of Trojans for J2ME is an event equal in significance to the discovery of the very first worm for smartphones in June 2004. It is difficult to evaluate the threat precisely; however, given that there are a lot more regular phones in the world than smartphones, the existence of malware that successfully infects regular phones bodes nothing good. Regular phones will now require antivirus protection as well as their more advanced brethren.

Hybridization: a method for creating new malware families

The table below traces the appearance of new families of malware during the first half of 2006:

| Name | Date | Operating System | Function | Technology |

| Trojan-SMS.J2ME.RedBrowser | February | J2ME | Sends SMS | Java, SMS |

| Worm.MSIL.Cxover | March | .NET | Deletes files, copies self to other devices |

File (API), NetWork (API) |

| Worm.SymbOS.StealWar | March | Symbian | Steals data, spreads via Bluetooth and MMS |

Bluetooth, MMS, File (API) |

| Email-Worm.MSIL.Letum | March | .NET | Spreads via email | Email, File (API) |

| Trojan-Spy.SymbOS.Flexispy | April | Symbian | Steals data | — |

| Trojan.SymbOS.Rommwar | April | Symbian | Disables system functions, replaces icons |

Operating system vulnerability |

| Trojan.SymbOS.Arifat | April | Symbian | — | — |

| Trojan.SymbOS.Romride | June | Symbian | Replaces system applications | Operating system vulnerability |

Diagram 2. Increases in known mobile malware families |

Hybridization continues to be one of the most important factors behind the creation of new mobile malware. StealWar is a particularly good example: it is basically a combination of two earlier malicious programs – the Pbstealer Trojan-spy and the Comwar worm. The author of StealWar combined them into one module to create a worm that possessed the characteristics of both ‘parents’: it both spreads via MMS and steals data from local address books. Many variants of Skuller and SingleJump demonstrated similar mutations, as both contain elements from the Cabir worm. Such mutations are an ongoing headache for security vendors, as they complicate classification.

The calm before the storm?

As noted above, the second quarter of 2006 saw a lull in the growth rate of new samples – both for known and new malware families.

From the moment of its first appearance two years ago, mobile malware developed at an even pace and was predictable since it followed the evolving capabilities of smartphones. The dynamics of mobile malware growth changed noticeably only a few months ago, which makes it difficult to make exact predictions at this point. Nevertheless, a preliminary evaluation is necessary.

Blackhat malware writers are always to be found in the vanguard of any new developments. Mobile malware is still a relatively new area, wholly dependent on blackhats for further exploration. Thus, the lull in the appearance of additional proof of concept malware for mobile devices is a possible sign that blackhats have moved on to a more appealing target. The new vulnerabilites in MS Office applications that have been published in the late spring and early summer could well prove to be such a target.

Antivirus experts have long known that in addition to amateur blackhat malware writers, the virus writing world consists of two other significant groups: professionals and script kiddies. The former write malware for profit, while the latter are minimally qualified techno freaks who use ready-made code to create their own rather primitive versions of existing malware.

To date, professional malware writers have not yet had their say as far as mobile malware is concerned. The majority of mobile phones in use today are of medium technological complexity, ranging from regular phones to smartphones. So far, these devices have not presented any opportunity to create a significant commercial piece of malware. Moreover, none of these devices have enough memory to store the type of vulnerable data that would interest the professional. Nevertheless, the first sign that professionals are interested in mobile malware was the appearance of the Flexispy Trojan, which sends the author SMS and phone call logs.

Script kiddies depend on the above two groups to create malware, so they are correspondingly quiet, perhaps tired of writing primitive DoS- Trojans for Symbian.

In short, the lull in mobile malware is obviously temporary. Sales of smartphones are rising andtheir capabilities are broadening, therefore further expansion of malware writers in this area is inevitable. Time, specifically the fall and winter of 2006-2007, will tell whether this lull is truly the calm before the storm.

Trends

Mobile malware development is directly linked to how widespread mobile devices are throughout the world. Once the number of smartphones and similar devices is equal to the number of PCs in the world, we will start to see corresponding numbers of malware targeted at them.

According to data from IDC almost 19 million smartphones were purchased during the first 3 months of 2006, which constitutes a rise of over 67% relative to the same period in 2005. And it is likely that this trend will continue throughout 2006.

An estimated 50 million smartphones have been sold so far, 40-50% of them by Nokia. Nokia runs under Symbian, currently the most popular operating system for mobile malware, including Cabir and ComWar. Almost 100% of all mobile malware is designed to run under Symbian, and consequently Symbian will continue to be the target for cyber criminals for at least the next six months.

It is envisaged that the number of smartphones will reach 100 million or so by early 2007. Virus writers are highly likely to pay close attention to such a large number of potential victims.

During InfoSecurity London in April of this year, Kaspersky Lab conducted research into the distribution of smartphones, their makers and operating systems. The complete results are available online at https://securelist.com/bluetooth-london-2006/36087/.

In short, approximately 23% of mobile devices running Bluetooth are smartphones. 80% of these support the Object Transfer function, which is necessary for the spread of mobile malware that uses Bluetooth such as Cabir, ComWar, PBStealer, Skuller and so forth. This brings up a key issue in contemporary mobile device security: the use of Bluetooth.

Leaving a Bluetooth enabled device in discoverable mode leaves the device open not only to infection by malware, but also to attack by hackers exploiting one of the many documented vulnerabilties in Bluetooth itself. In the current climate, users should not only continue to use Bluetooth in invisible mode only, but should also be careful with incoming MMS.

Windows Mobile is the second most popular operating system for mobile devices after Symbian, and is gaining ground rapidly. This will undoubtedly be reflected in the relative numbers of Symbian and WinMobile malware. Moreover, it is easier to code WinMobile malware, due to its similarity to regular Windows platforms, as well as the quantity of readily available information and programming tools.

Naturally, antivirus vendors are on their guard. Most vendors have released new products and beta versions that are designed to protect smartphones or providers from mobile malware. The list includes the Kaspersky Anti-Virus Mobile beta, betas from BitDefender and ESET, Trend Micro’s WinMobile antivirus and McAfee’s solutions for mobile providers and customers.

As mobile malware becomes more prevalent, antivirus protection for mobile devices is becoming an increasingly essential component for any security system that aims to protect networks comprehensively and effectively.

Kaspersky Security Bulletin, January – June 2006: Malicious programs for mobile devices