- Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2012. Malware Evolution

- Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2012. The overall statistics for 2012

Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2012. Cyber Weapons

Before 2012, there were only two instances of cyber weapons being used – Stuxnet and Duqu. However, analysis of these two forced the IT community to dramatically expand the whole concept of what cyber warfare entails.

Apart from an increase in the number of security incidents involving cyber weapons, the events of 2012 have also brought to light the fact that many sovereign states are heavily involved in the development of cyber weapons – something that was picked up on and widely discussed by the mass media.

Moreover, cyber warfare was on the agenda of public discussions between governments and state representatives over the course of 2012.

It is safe to say, therefore, that 2012 has brought key revelations in this sphere – both in terms of the increase in security incidents and a greater understanding of how cyber weapons are being developed.

World view

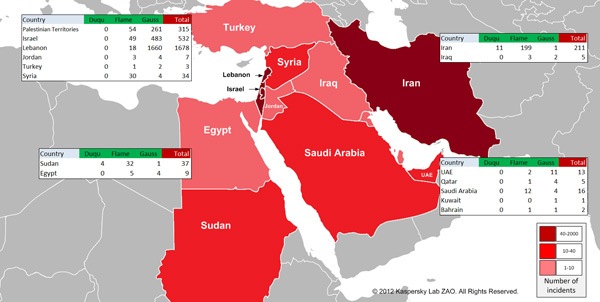

2012 saw the use of cyber weapons spread to a wider area. Previously they had only targeted Iran, but throughout the year they were deployed in a broader region of Western Asia adjacent to Iran. This change reflected the political developments in a region that has long been regarded as volatile.

Iran’s nuclear program continued, while the situation in the region was further complicated by political crises in Syria and Egypt. Tensions in Lebanon, the on-going Israeli-Palestinian conflict and unrest in several countries around the Persian Gulf merely added to the instability across the region.

In these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that other nations have sought to defend their interests and have used all available tools to both defend themselves and gather information.

All these factors combined have sparked several serious incidents in the region which, after closer analysis, can be classified as the application of cyber weapons.

Duqu

This malicious spyware program, which was detected in September 2011 and brought to public attention in October 2011, prompted Kaspersky Lab’s experts to action. As part of their research, the company’s experts managed to gain access to a number of Duqu’s C&C servers and collect a substantial amount of information about the programs’ architecture and its evolution. It was convincingly demonstrated that Duqu was a development of the Tilded platform, on the basis of which another high-profile malicious program – Stuxnet – had also been developed. Besides, it was established that at least three more malware programs existed that used the same Duqu/Stuxnet framework; this malware has yet to be detected.

The research activity prompted Duqu’s operators to destroy all traces of their activity from the C&C servers and victim computers.

By late 2011, Duqu ceased to exist “in the wild”. However, in late February 2012 Symantec’s experts discovered a new version of a driver in Iran, similar to the one used in Duqu but created on 23 February, 2012. The core module was never detected; no further modifications of Duqu have been discovered since then.

Wiper

This “mystical” Trojan greatly disturbed Iran in late April 2012: it emerged basically from nowhere and destroyed a large number of databases in dozens of organizations. The country’s largest oil depot was especially hard hit – its operation was halted for several days after data on oil contracts was destroyed.

However, not a single sample of the malicious program used in these attacks was detected, which prompted many to question the accuracy of media reports.

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) asked Kaspersky Lab to research these incidents and determine the potential damage wrought by this malicious program.

Wiper’s creators did their best to destroy all the data that could be used to analyze the incidents. For this reason, practically no traces of the malicious program’s activity were left after Wiper was activated.

In the course of investigating the mysterious malicious attack in April, we managed to obtain and analyze samples of several hard drives attacked by Wiper. We can confirm that these incidents did indeed take place and that the malicious program used in these attacks existed in April 2012. Moreover, we know of several very similar incidents that have taken place, dating back to December 2011.

The bulk of the attacks took place in the final 10 days of a month (from the 21st to the 30th); however, we cannot be certain that there was a dedicated function that was only activated on specific dates.

Several weeks into the investigation, we were still unable to detect any malicious files whose properties matched the known characteristics of Wiper. However, we did discover a cyber-espionage campaign being conducted on a state level, which is now known as Flame; later on, we discovered yet another cyber-espionage system that was subsequently dubbed Gauss.

Flame

Flame is a very sophisticated toolkit for conducting attacks, far more complex than Duqu. It is a backdoor Trojan which also possesses some of the characteristic of worms; the latter enable it to propagate via local networks or removable storage drives following instructions from its master.

After infecting the host system, Flame starts to execute a complex set of operations, which can include analyzing the network traffic, taking screenshots, recording voice communications, keystroke logging etc. All this data is available to its operators via Flame C&C servers.

The operators can also download extra modules to victim computers to extend Flame’s payload. All in all, 20 extension modules were detected.

Flame incorporated a unique functionality to propagate itself across a LAN; to that end, it intercepted Windows update requests and substituted them with its own module signed with a Microsoft certificate. Analysis of this certificate revealed a unique cryptographic attack which enabled cybercriminals to generate their own bogus certificate that was indistinguishable from a legal one.

The information we have collected testifies that the development of Flame started back in 2008 or so, and continued actively right up to its exposure in May 2012.

Moreover, we were able to establish that one of the modules created on the Flame platform was used in 2009 as a propagation module for the Stuxnet worm. This fact demonstrates that there has been close cooperation between the programming teams of the Flame and Tilded platforms, right up to the exchange of source code.

Gauss

After we discovered Flame we implemented several heuristic methods based on an analysis of similarities in the code. This approach soon brought us another breakthrough. In mid-July, a malicious program was detected that had been created on the Flame platform; however, it had a different payload and habitat.

Gauss is a sophisticated toolkit for conducting cyber espionage, implemented by the same group that created the malicious Flame platform. The toolkit has a modular structure and supports remote deployment of a new payload that is implemented in the form of extra modules. The modules found so far perform the following functions:

- Intercept cookie-files and passwords in the web browser;

- Collect system configuration data and send it to cybercriminals;

- Infect USB storage drives with a module designed to steal data;

- Create lists of the contents on a system’s storage drives and folders;

- Steal data required to access user accounts of various banking systems in the Middle East;

- Intercept account data in social networks, mailing and instant messaging services.

It seems the modules were named in honor of renowned mathematicians and philosophers – Kurt Gödel, Carl Friedrich Gauss and Joseph Louis Lagrange.

Based on the results of our analysis and the timestamps in the malicious modules available to us, we concluded that Gauss started operating in August or September 2011.

Since late May 2012, Kaspersky Lab’s cloud-based security service has registered over 2500 Gauss infections; we estimate that the actual total number of Gauss victims may be in the tens of thousands.

The vast majority of Gauss victims are Lebanese residents; victims were also registered in Israel and the Palestinian territories. Smaller numbers of victims were recorded in the USA, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Jordan, Germany and Egypt.

miniFlame

In early June 2012, we discovered a small yet interesting module created on the Flame platform. This malicious program, dubbed miniFlame, is a miniature fully-fledged spyware module designed to steal information and gain access to an infected system. Unlike Flame and Gauss, which were both used to carry out large-scale espionage operations with thousands of users being infected, miniFlame/SPE is a tool for carrying out targeted attacks with pinpoint accuracy.

Although miniFlame is based on the Flame platform, it is implemented as a stand-alone module that can operate both autonomously, without Flame’s main modules being present in the system, and as a component controlled by Flame. Remarkably, miniFlame can also be used in conjunction with Gauss, another spyware program.

It appears that the development of miniFlame began several years ago and continued until 2012. Judging by its C&C code, the protocols for servicing SP and SPE were created earlier than, or at the same time as, the operation protocol for FL (Flame), which means no later than 2007.

miniFlame’s primary purpose is to function as a backdoor on infected systems, enabling attackers to directly manage them.

The number of miniFlame victims is comparable to that of Duqu.

| Name | Number of incidents (Kaspersky Lab statistics) | Approximate number of incidents |

| Stuxnet | Over 100 000 | Over 300 000 |

| Gauss | ~ 2500 | ~10 000 |

| Flame (FL) | ~ 700 | ~5000-6000 |

| Duqu | ~20 | ~50-60 |

| miniFlame (SPE) | ~10-20 | ~50-60 |

A summary of all the data about malicious programs classed as “cyber weapons” discovered in 2012, demonstrates a clear geographic connection with the Middle East.

So what does it all mean?

Our experience of detecting and analyzing all of the malware discussed above enables us to put forward the following view on contemporary threats and their classification.

The current state of malware is best represented as a pyramid.

The base of the pyramid is made up of all kinds of threats – what we call ‘traditional’ cybercrime. Its distinguishing features include a reliance of mass attacks targeting ordinary users. Cybercriminals’ are mostly interested in launching these attacks for direct financial gain. Malware in this tier includes banking Trojans, clickers, botnets, ransomware, mobile threats etc. and accounts for over 90% of all contemporary threats.

The second tier is made up of threats aimed at organizations. These are targeted attacks, which include industrial espionage, as well as targeted hacker attacks designed to discredit their victims. The attackers are highly specialized and work with a specific target in mind or for a specific client. The goal is to steal information or intellectual property. Financial gain is not the attackers’ primary goal. According to our classification, this group of threats also includes a variety of malicious programs created by certain companies at the request of law enforcement agencies in several countries and sold almost openly, e.g. malware developed by the Gamma Group or Hacking Team SRL.

The third tier, which is the top level of the pyramid, includes malware which can be categorized as true cyber weapons. In our classification, this includes malware created and financed by government-controlled structures. Such malware is used against citizens, organizations and agencies in other countries.

Based on all the samples of such programs that we know of, we can identify three main groups of threats in this category:

- ‘Destroyers’. These are programs designed to destroy databases and information as a whole. They can be implemented as ‘logic bombs’ that are introduced into victim systems either in advance and then triggered at a certain time, or during a targeted attack with immediate execution. The most notable example of such malware is Wiper.

- Espionage programs. This group includes Flame, Gauss, Duqu and miniFlame. The primary purpose of such malware is to collect as much information as possible, particularly very highly specialized data (e.g. from Autocad projects, SCADA systems etc.), which can then be used to create other types of threats.

- Cyber sabotage tools. These are the ultimate form of cyber weaponry – threats resulting in physical damage to targets. Naturally, this category includes the Stuxnet worm. Threats of this kind are unique and we believe they are always going to be a rare phenomenon. However, some countries are devoting more and more effort to developing this type of threat, as well as defending themselves against it.

Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2012. Cyber Weapons