The identity of the companies targeted by the first known cyber-weapon

The Stuxnet cyber-sabotage operation remains one of the favorite discussion subjects of security researchers everywhere. Considered the first known cyber-weapon, Stuxnet targeted the Iranian nuclear program using a subtle and well designed mechanism.

For background, see our previous reports on the Stuxnet saga:

- The Day The Stuxnet Died

- Myrtus and Guava: Episode 1

- Myrtus and Guava: Episode 2

- Myrtus and Guava, Episode 3

- Myrtus and Guava, Episode 4

- Myrtus and Guava: Episode 5

- Myrtus and Guava, Episode MS10-061

- Myrtus and Guava: the epidemic, the trends, the numbers

- Back to Stuxnet: The Missing Link

One of the reasons to revisit the Stuxnet subject is the publication (November 11th, 2014) of the book “Countdown to Zero Day” by journalist Kim Zetter.

We are quite excited about the book which includes new and previously undisclosed information about Stuxnet. Some of the information is actually based on interviews conducted by Kim Zetter with members of Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research and Analysis Team. To complement the book release, we’ve decided to also publish new technical information about some previously unknown aspects of the Stuxnet attack.

Even though Stuxnet was discovered more than four years ago, and has been studied in detail with the publication of many research papers. However, is still not known for certain what object was originally targeted by the worm. It is most likely that Stuxnet was intended to affect the motors that drive uranium enrichment centrifuges. But where were those centrifuges located – in the Natanz plant or, perhaps, in Fordow? Or some other place?

The story of the earliest known version of the worm – “Stuxnet 0.5” – is outside the scope of this post; we are going to focus on the best known variants created in 2009 and 2010. (The differences between them are discussed in our 2012 publication – Back to Stuxnet: the missing link).

In February 2011, Symantec published a new version of its W32.Stuxnet Dossier report. After analyzing more than 3,000 files of the worm, Symantec established that Stuxnet was distributed via five organizations, some of which were attacked twice – in 2009 and 2010.

Screenshot from the Symantec report

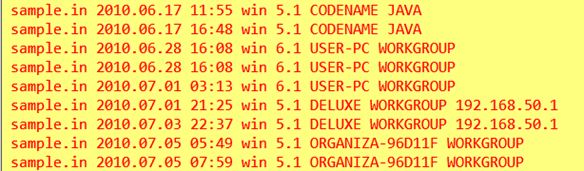

The Symantec experts were able extract this information due to a curious feature of the worm. When infecting a new computer, Stuxnet saves information about the infected system’s name, Windows domain and IP address. This information is stored in the worm’s internal log and is augmented with new data when the next victim is infected. As a result, information on the path travelled by the worm can be found inside Stuxnet samples and used to establish from which computer the infection began to spread.

Example of information found in a Stuxnet file

While Symantec did not disclose the names of the organizations in its report, this information is essential for a proper understanding of how the worm was distributed.

We collected Stuxnet files for two years. After analyzing more than 2,000 of these files, we were able to identify the organizations that were the first victims of the worm’s different variants in 2009 and 2010. Perhaps an analysis of their activity can explain why they became “patients zero” (the original, or zero, victims).

“Domain A”

The Stuxnet 2009 version (we will refer to it as Stuxnet.a) was created on June 22, 2009. This information is present in the worm’s body – in the form of the main module’s compilation date. Just a few hours after that, the worm infected its first computer. Such a short time interval between creating the file and infecting the first computer almost completely rules out infection via USB drive – the USB stick simply can’t have passed from the worm’s authors to the organization under attack in such a short time.

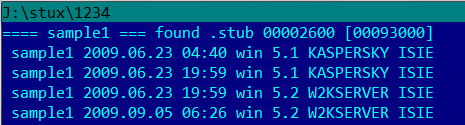

The infected machine had the name “KASPERSKY” and it was part of the “ISIE” domain.

When we first saw the computer’s name, we were very much surprised. The name could mean that the initial infection affected some server named after our anti-malware solution installed on it. However, the name of the local domain, ISIE, provided us with a little bit of information that might help to determine the organization’s real name.

Assuming that the victim was located in Iran, we conjectured that it could be the Iranian Society of Industrial Engineers (ISIE) or an organization affiliated with it, the Iranian institute of Industrial Engineering (IIIE). But could it have been some other ISIE located in some place other than Iran? Given that our anti-malware solution had been used on the infected computer, we considered the possibility that ISIE might even be a Russian company.

It took us a long time to establish what organization it really was, but ultimately we succeeded in identifying it with a high degree of certainty.

It is called Foolad Technic Engineering Co (FIECO). It is an Iranian company with headquarters in Isfahan. The company creates automated systems for Iranian industrial facilities (mostly those producing steel and power) and has over 300 employees.

Screenshot from the company’s website

The company is directly involved with industrial control systems.

– Implementing bench scale and pilot scale projects, such as data

communication between PLC existing in a plant and a remote point

through internet, by defining home page on a CP (Communication Processor)

card connected to a S7 CPU.

– Implementing different network structures, such as, As interface, profibus

DP, Ethernet, MPI, profibus PA In electronic and light communication channels.

Clearly, the company has data, drawings and plans for many of Iran’s largest industrial enterprises on its network. It should be kept in mind that, in addition to affecting motors, Stuxnet included espionage functionality and collected information on STEP 7 projects found on infected systems.

In 2010, that same organization was attacked again – this time using the third version of Stuxnet, created on April 14, 2010. On April 26, the same computer as in 2009 – “KASPERSKY.ISIE” – was infected again.

This persistence on the part of the Stuxnet creators may indicate that they regarded Foolad Technic Engineering Co. not only as one of the shortest paths to the worm’s final target, but as an exceptionally interesting object for collecting data on Iran’s industry.

“Domain B”

One more organization was attacked multiple times – once in 2009 and twice in 2010. Essentially, each of the three Stuxnet variants was used to infect this target. In this case, the attackers were even more persistent than in the case of Foolad Technical Engineering Co.

It should be noted that it was this victim that was the patient zero of the 2010 global epidemic. This organization’s infection in the course of the second attack (in March 2010) led to the widest distribution of Stuxnet – first in Iran, then across the globe. Curiously, when that same organization was infected in June 2009 and in May 2010, the worm hardly spread at all. We share our thoughts on the reasons for that below.

Take the most widespread variant – Stuxnet 2010 (a.k.a. Stuxnet.b). It was compiled on March 1, 2010. The first infection took place three weeks later – on March 23.

In addition to the computer’s name and the domain name, Stuxnet has recorded the machine’s IP number. The fact that the address changed on March 29, may indicate, albeit indirectly, that it was a laptop which connected to the company’s local network once in a while.

But what company is it? The domain name –”behpajooh” – immediately gives us the answer: Behpajooh Co. Elec & Comp. Engineering.

Like Foolad Technic, this company is located in Isfahan and it also develops industrial automation systems. Clearly, we are also dealing with SCADA/PLC experts here.

Screenshot from the company’s website

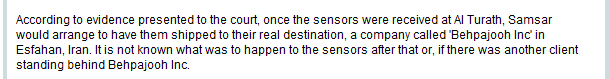

While collecting information about Behpajooh Co, we discovered one more curious thing – a 2006 article published in a Dubai (UAE) newspaper called Khaleej Times.

According to the article, a Dubai firm was accused of smuggling bomb components into Iran. The Iranian recipient of the shipment was also named – it was a certain “Bejpajooh Inc” from Isfahan.

So why did Stuxnet spread most actively as a result of the March 2010 Behpajooh infection? We believe the answer lies in the second organization in the chain of infections that started from Behpajooh.

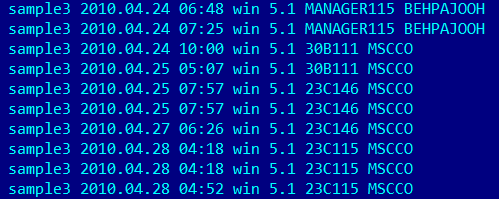

As the screenshot above shows, on April 24, 2010 Stuxnet spread from the corporate network of Behpajooh to another network, which had the domain name MSCCO. A search for all possible options led us to the conclusion that the most likely the victim is Mobarakeh Steel Company (MSC), Iran’s largest steel maker and one of the largest industrial complexes operating in Iran, which is located not far from Isfahan, where the two victims mentioned above – Behpajooh and Foolad Technic – are based.

Stuxnet infecting the industrial complex, which is clearly connected to dozens of other enterprises in Iran and uses an enormous number of computers in its production facilities, caused a chain reaction, resulting in the worm spreading across thousands of systems in two or three months. For example, the analysis of logs shows that by July 2010 this branch of the infection reached computers in Russian and Belarusian companies.

“Domain С”

On July 7, 2009, Stuxnet 2009 hit yet another target. With it, it was designed to start the path to its ultimate intended mission. The victim computer was named “applserver” (application server?), located in the domain NEDA.

In this case, it was pretty easy to identify the victim organization. Beyond any doubt, it was the Neda Industrial Group, an organization that was put on the sanctions list by the U.S. Ministry of Justice, and charged with the illegal export of prohibited entities into Iran with potential military applications. This company’s complete dossier is available on the Iran Watch site.

When tracking the chain of Stuxnet propagation, one of the group’s branch organizations raises special interest: “Allegedly the controlling entity of Nedaye Micron Electronic Company in Tehran, Iran and Neda Overseas Electronics LLC in Dubai, UAE; provides services in industrial automation for power plants, the cement industry, and the oil, gas and petrochemical sector; established in the mid 1980s under the name NEDA Computer Products Incorporated as a fully private joint stock company”.

Neda was attacked only once, in July 2009, and Stuxnet never left that organization, according to the infection logs available to us. However, to leave the organization may have not been its purpose in this case. As noted earlier, the capability of stealing information about STEP 7 projects from infected systems was of special interest to the creators of Stuxnet.

“Domain D”

The fourth victim in 2009 was infected on July 7, the same day when Neda was compromised. Interestingly, the infection started with the server, if we judge by the computer name – SRV1 in domain CGJ, just like it did in the Neda case.

So, what is CGJ? We spent quite some time combing through search engines and social networks, and we are practically confident that is Control-Gostar Jahed Company, another Iranian company operating in industrial automation.

Control Gostar Jahed (CGJ) (Private Joint Stock, Since 1383) Founded with the aim of localization of industrial automation technology, and employing the technical know-how and execution power of 30 full-time personnel in the Tehran office and more than 50 workshop personnel, has achieved a high capacity in providing engineering and technical services.

The companys major focus over the years has been on the following domains:

– Design, procurement, construction, programming and commissioning of control systems (DCS, PLC, ESD, F&G)

– Design, manufacture and installation of low voltage fixed and sliding panels (using the products of CUBIC Denmark)

– Upgrading hardware, software and optimization of industrial automation systems

– Consulting services and basic and detailed design of electrical and instrumentation systems

– Installation of electrical and control systems

Unlike Neda Group, Control-Gostar Jahed Company is not on the sanctions list. It was probably chosen as a target because of its impressive cooperation ties with the largest Iranian businesses in oil production, metallurgy and energy supplies.

This organization was attacked only once in 2009. That infection did not leave the target’s corporate network and makes up the smallest part of all known Stuxnet propagation lines.

“Domain E”

The fifth and the last “Patient Zero” victim stands out when judged by the numbers of originally infected systems. Unlike in all above cases, the attack in this case started from three computers at once, on the same day (May 11, 2010), but at different times.

Information from three different Stuxnet files

KALASERVER, ANTIVIRUSPC, NAMADSERVER: judging by the names, there were at least two servers involved in this case too.

Such an pattern of infection makes us practically confident that email was not used as the primary infection vector. The chances are very small that the infection started from a user receiving an email containing an attachment with an exploit.

So what is Kala? There are two most verisimilar answers to this, and we do not know which is the correct one. Both are about companies affected by sanctions and directly related to Iran’s nuclear program.

Well, one possibility could be Kala Naft. A dossier for this company is available on the Iran Watch site.

However, Kala Electric (a.k.a. Kalaye Electric Co.) looks like the most probable victim. This is in fact an ideal target for an attack, given Stuxnet’s main objective (which is to render uranium enrichment centrifuges inoperable), available information on Iran’s nuclear program, and the logic of the worm’s propagation.

Of all other companies, Kala Electric is named as the main manufacturer of the Iranian uranium enrichment centrifuges, IR-1.

The company does not have a web-site, but there is quite some information available about its activities: that is one of the key structures within the entire Iranian nuclear program.

Also, quite detailed information is available on the ISIS (Institute for Science and International Security) site at www.isisnucleariran.org.

Based on Iran’s revised declaration about this site, originally, Kalaye Electric was a private company that was bought by the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI). The name “Kalaye Electric” means “electric goods,” implying that Iran kept the original name to help disguise the true purpose of the facility.

Iran declared that Kalaye Electric became the primary IR-1 centrifuge development and testing site after such work was moved in 1995 from the Tehran Nuclear Research Center. The IAEA has reported that between 1997 and 2002, Iran assembled and tested IR-1 centrifuges at Kalaye

Since moving many centrifuge research and development activities to the Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (PFEP) at Natanz, Kalaye Electric has remained an important centrifuge research and development site.

Satellite images of Kala Electric operation facilities are also available; these are considered to be the site where the centrifuges were developed and tested.

Source: http://www.isisnucleariran.org/sites/detail/kalaye/

Thus, it appears quite reasonable that this organization of all others was chosen as the first link in the infections chain intended to bring the worm to its ultimate target. It is in fact surprising that this organization was not among the targets of the 2009 attacks.

Summary

Stuxnet remains one of the most interesting pieces of malware ever created. In the digital world, one might say it is the cyber equivalent of the atomic attacks on Nagasaki and Hiroshima from 1945.

For Stuxnet to be effective and penetrate the highly guarded installations where Iran was developing its nuclear program, the attackers had a tough dilemma to solve: how to sneak the malicious code into a place with no direct internet connections? The targeting of certain “high profile” companies was the solution and it was probably successful.

Unfortunately, due to certain errors or design flaws, Stuxnet started infecting other organizations and propagate over the internet. The attackers lost control of the worm, which infected hundreds of thousands of computers in addition to its designated targets.

Of course, one of the biggest remaining questions is – were there any other malware like Stuxnet, or was it one-of-a-kind experiment? The future will tell for sure.

Stuxnet: Zero victims

Weber Ress

Great article !

Morgan Robertson

Great article.

Matthieu Aubigny

Very interesting paper.

Tinel

It looks like Stuxnet was created by Kaspersky and the beneficiary is Russian government.

Thanks for clarify that.

What about Dyre and Carbanak?

Patrick Hunter

…..that’s a conspiracy theory I haven’t heard yet. I hope you get an email notification from this reply so you can come back and entertain me with an explanation of why you think that.