In our previous blog, we detailed our findings on the attack against the Pyeongchang 2018 Winter Olympics. For this investigation, our analysts were provided with administrative access to one of the affected servers, located in a hotel based in Pyeongchang county, South Korea. In addition, we collected all available evidence from various private and public sources and worked with several companies to investigate the command and control (C&C) infrastructure associated with the attackers.

During this investigation, one thing stood out – the attackers had pretty good operational security and made almost no mistakes. Some of our colleagues from other companies pointed out similarities with Chinese APT groups and Lazarus. Yet, something about these potential connections didn’t quite add up. This made us look deeper for more clues.

The attackers behind OlympicDestroyer employed several tricks to make it look similar to the malicious samples attributed to the Lazarus group. The main module of OlympicDestroyer carries five additional binaries in its resources, named 101 to 105 respectively. It is already known that resources 102 and 103, with the internal names ‘kiwi86.dll’ and ‘kiwi64.dll’ share considerable amounts of code with other known malware families only because they are built on top of the Mimikatz open-source tool. Resource 105, however is much more interesting in terms of attribution.

Resource 105 is the ‘wiper‘ component of OlympicDestroyer. This binary launches a destructive attack on the victim’s network; it removes shadow copy backups, traverses the shared folders on the networks and wipes files. Anyone familiar with the wipers attributed to the Lazarus group will find strong similarities in the file deletion routines:

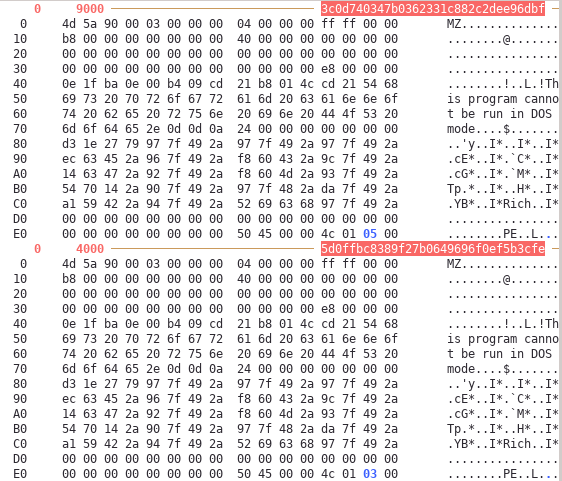

File deletion routines.

To the left 3c0d740347b0362331c882c2dee96dbf (OlympicDestroyer), on the right 1d0e79feb6d7ed23eb1bf7f257ce4fee (BlueNoroff by Lazarus).

Both functions do essentially the same thing: they delete the file by wiping it with zeroes, using a 4096 bytes memory block. The minor difference here is that the original Bluenoroff routine doesn’t just return after wiping the file, but also renames it to a new random name and then deletes it. So, the similar code may be considered as no more than a weak link.

A much more interesting discovery appeared when we started looking for various kinds of metadata of the PE file. It turned out that that the wiper component of OlympicDestroyer contained the exact ‘Rich’ header that appeared previously in Bluenoroff samples.

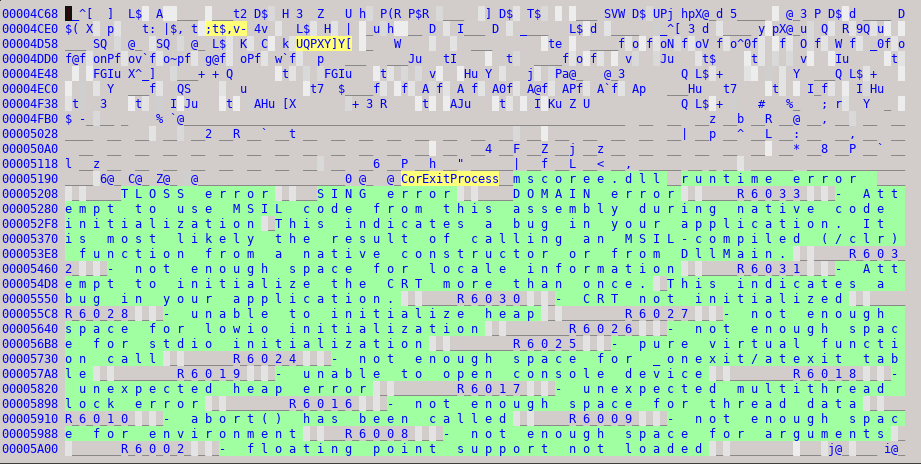

MZ DOS and Rich headers of both files (3c0d740347b0362331c882c2dee96dbf – OlympicDestroyer, 5d0ffbc8389f27b0649696f0ef5b3cfe – BlueNoroff) are exactly the same.

This provided us with an interesting clue: if files from both the OlympicDestroyer and Bluenoroff families shared the same Rich header it meant that they were built using the same environment and, having already found some similarities in the code, this could have meant that there is a real link between them. To test this theory, we needed to investigate the contents of the Rich header.

The Rich header is an undocumented structure that appears in most of the PE files generated with the ‘LINK.EXE’ tool by Microsoft. Effectively, any binary built using the standard Microsoft Visual Studio toolset contains this header. There is no official documentation describing this structure, but there is enough public information that can be found on the internet, and there is also the LINK.EXE itself that can be reverse engineered. So, what is a Rich header?

A Rich header is a structure that is written right after the MZ DOS header. It consists of pairs of 4-byte integers. It starts with the magic value, ‘DanS’ and ends with a ‘Rich’ followed by a checksum. And it is also encrypted using a simple XOR operation using the checksum as the key. The data between the magic values encodes the ‘bill of materials’ that were collected by the linker to produce the binary.

| Offset | First value | Second value | Description |

| 00 | 44 61 6E 53 (“DanS”) | 00 00 00 00 | Beginning of the header |

| 08 | 00 00 00 00 | 00 00 00 00 | Empty record |

| 10 | Tool id, build version | Number of items | Bill of materials record #1 |

| … | |||

| … | 52 69 63 68 “Rich” | Checksum / XOR key | End of the header |

The first value of each record is a tool identifier: the unique number of the tool (‘C++ compiler’, ‘C compiler’, ‘resource compiler’, ‘MASM’, etc.), a Visual Studio specific, and the lowest 16 bits of the build number of the tool. The second value is a little-endian integer that is a number of items that were produced by the tool. For example, if the application consists of three source C++ files, there will be a record with a tool id corresponding to the C++ compiler, and the item count will be exactly ‘3’.

The Rich header in OlympicDestroyer’s wiper component can be decoded as follows:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

Raw data Type Count Produced by ======================================================== 000C 1C7B 00000001 oldnames 1 12 build 7291 000A 1F6F 0000000B cobj 11 VC 6 (build 8047) 000E 1C83 00000005 masm613 5 MASM 6 (build 7299) 0004 1F6F 00000004 stdlibdll 4 VC 6 (build 8047) 005D 0FC3 00000007 sdk/imp 7 VC 2003 (build 4035) 0001 0000 0000004D imports 77 imports (build 0) 000B 2636 00000003 c++obj 3 VC 6 (build 9782) |

It is a typical example of a header for a binary created with Visual Studio 6. The ‘masm613’ items were most likely taken from the standard runtime library, while the items marked as ‘VC 2003’ correspond to libraries imported from a newer Windows SDK – the code uses some Windows API functions that were missing at the time VC 6 was released. So, basically it looks like a C++ application having three source code files and using a slightly newer SDK to link the Windows APIs. The description perfectly matches the contents of the Bluenoroff sample that has the same Rich header (i.e. 5d0ffbc8389f27b0649696f0ef5b3cfe).

We get very different results when trying to check the validity of the Rich header’s entries against the actual contents of OlympicDestroyer wiper’s component. Even a quick visual inspection of the file shows something very unusual for a file created with Visual Studio 6: references to ‘mscoree.dll’ that did not exist at the time.

After some experimentation and careful comparison of binaries generated by different versions of Visual Studio, we can name the actual version of Studio that was used: it is Visual Studio 2010 (MSVC 10). Our best proof is the code of the ___tmainCRTStartup function that is only produced with the runtime library of MSVC 10 (DLL runtime) using default optimizations.

Beginning of the disassembly of the ___tmainCRTStartup function of the OlympicDestroyer’s wiper component, 3c0d740347b0362331c882c2dee96dbf

It is not possible that the binary was produced with a standard linker and was built using the MSVC 2010 runtime, having the 2010’s startup code invoking the WinMain function and at the same time did not have any Rich records referring to VC/VC++ 2010. At the same time, it could not have the same number of Rich records for the VC6 code that is missing from the binary!

A binary produced with Visual Studio 2010 and built from the same code (decompiled), having the same startup code and almost identical to the wiper’s sample will have a Rich header that is totally different:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

Raw data Type Count Produced by ================================================================ 009E 9D1B 00000008 masm10 8 VC 2010 (build 40219) 0093 7809 0000000B sdk/imp 11 VC 2008 (build 30729) 0001 0000 00000063 imports 99 imports (build 0) 00AA 9D1B 0000003A cobj 58 VC 2010 (build 40219) 00AB 9D1B 0000000E c++obj 14 VC 2010 (build 40219) 009D 9D1B 00000001 linker 1 157 build 40219 |

The only reasonable conclusion that can be made is that the Rich header in the wiper was deliberately copied from the Bluenoroff samples; it is a fake and has no connection with the contents of the binary. It is not possible to completely understand the motives of this action, but we know for sure that the creators of OlympicDestroyer intentionally modified their product to resemble the Bluenoroff samples produced by the Lazarus group.

The forgotten sample

During the course of our investigation, we came across a sample that further consolidates the theory of the Rich header false flag from Lazarus.

The sample, 64aa21201bfd88d521fe90d44c7b5dba was uploaded to a multi-scanner service from France on 2018-02-09 13:46:23, as ‘olymp.exe’. This is a version of the wiper malware described above, with several important changes:

- The 60 minutes delay before shutdown was removed

- Compilation timestamp is 2018-02-09 10:42:19

- The Rich header appears legit

The removal of the 60 minutes’ delay indicates the attackers were probably in a rush and didn’t want to wait before shutting down the systems. Also, if true, the compilation timestamp 2018-02-09 10:42:19 puts it right after the attack on the Pyeonchang hotels, which took place at around 9:00 a.m. GMT. This suggests the attackers compiled this ‘special’ sample after the wiping attack against the hotels and, likely as a result of their hurry, forgot to fake the Rich header.

Conclusion

The existence of the fake Rich header from Lazarus samples in the new OlympicDestroyer samples indicates an intricate false flag operation designed to attribute this attack to the Lazarus group. The attackers’ knowledge of the Rich header is complemented by their gamble that a security researcher would discover it and use it for attribution. Although we discovered this overlap on February 13th, it seemed too good to be true. On the contrary, it felt like a false flag from the beginning, which is why we refrained from making any connections with previous operations or threat actors. This newly published research consolidates the theory that blaming the Lazarus group for the attack was parts of the attackers’ strategy.

We would like to ask other researchers around the world to join us in investigating these false flags and attempt to discover more facts about the origin of OlympicDestroyer.

If you would like to read more about Rich header, we can recommend a nice presentation on this from George Webster and Julian Kirsch or Technical University of Munich: https://infocon.hackingand.coffee/Hacktivity/Hacktivity%202016/Presentations/George_Webster-and-Julian-Kirsch.pdf.

IOCs:

3c0d740347b0362331c882c2dee96dbf – wiper with the fake Lazarus Rich header

64aa21201bfd88d521fe90d44c7b5dba – wiper the original Rich header and no delay before shutdown

The devil’s in the Rich header

yom

The link George Webster and Julian Kirsch’s slides looks dead.

The presentation is available here:

https://infocon.org/cons/Hacktivity/Hacktivity%202016/Presentations/George_Webster-and-Julian-Kirsch.pdf

george

Awesome blog post and really great finding. If curious about the rich header, the research paper might also be interesting. It goes into more details then the presentation.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318145388_Finding_the_Needle_A_Study_of_the_PE32_Rich_Header_and_Respective_Malware_Triage

0x100

Hello,Can I have some of samples for my research?