Ransomware has been targeting the private sector for years now.

Overall awareness of the need for security measures is growing, and cybercriminals are increasing the precision of their targeting to locate victims with security breaches in their defense systems. Looking back at the past three years, the share of users targeted with ransomware in the overall number of malware detections has risen from 2.8% to 3.5%. While this might seem like a modest amount, ransomware is capable of causing extensive damage in the affected systems and networks, which means this threat should never be overlooked. The proportion of ransomware targets among all users attacked with malware has been fluctuating, yet appears to be decreasing, with the figure for H1 2019 showing 2.94% compared to 3.53% two years ago.

Share of users attacked with ransomware from all users attacked with malware (download)

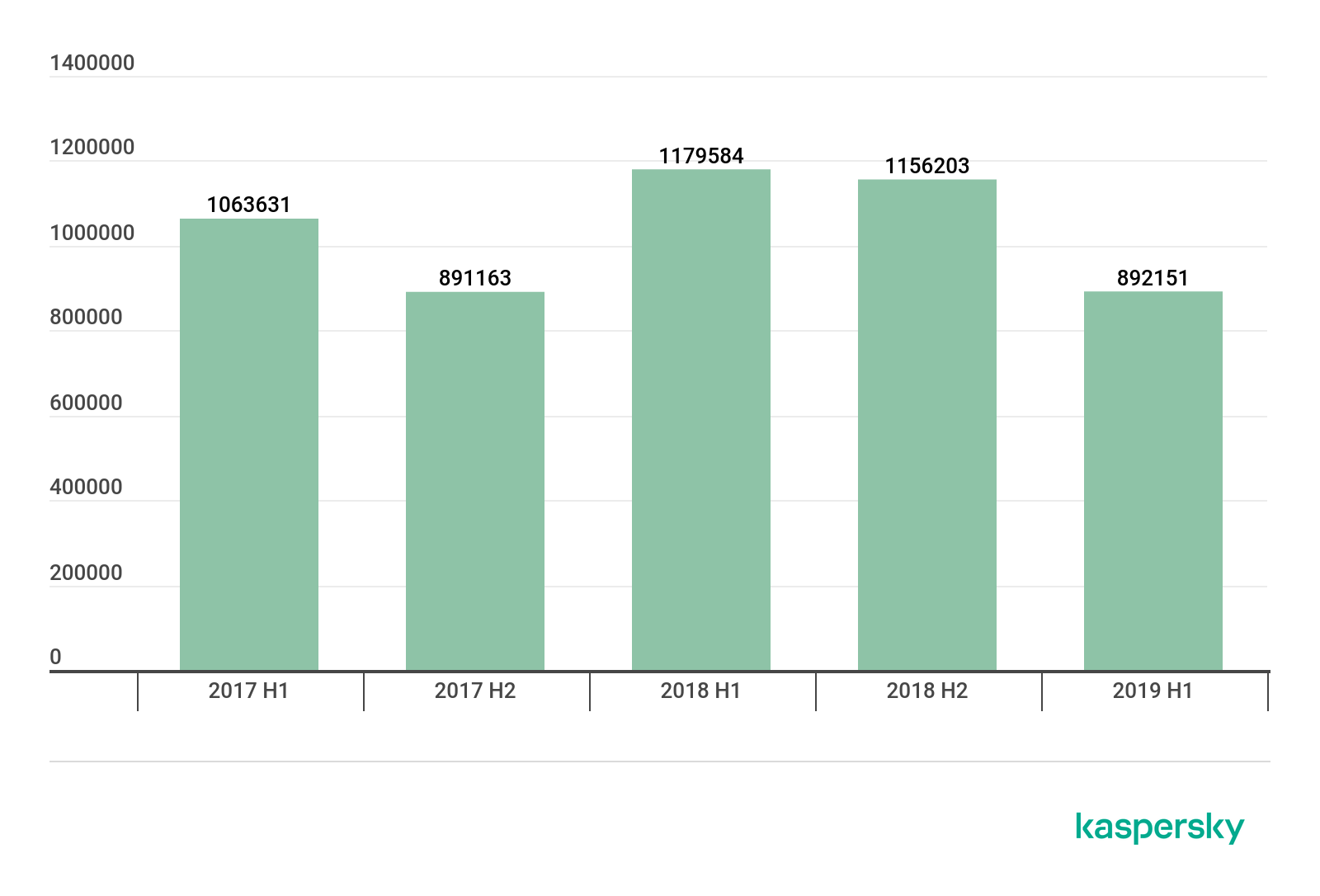

The overall number of users attacked annually has changed. Kaspersky experts usually observe from around 900,000 to almost 1.2 million users targeted by ransomware every six months.

Number of users attacked with ransomware, H1 2017-H1 2019 (download)

Despite there being many extremely sophisticated cryptor samples, the mechanism behind how they operate is painstakingly simple: they turn the files on victims’ computers into encrypted data and demand a ransom for the decryption keys. These keys are created by threat actors to decipher the files and transform them back into the original data. Without a key, it is impossible to operate the infected device. The malware may be distributed by the creators of the threat, sold to other actors or to the creators’ partner networks – ‘outsourced’ distributors that share the profit from successful ransomware attacks with the technology holders.

2019 has seen this plague actively shifting towards a new target – municipalities. Arguably, the most prominent and widely discussed incident was that in Baltimore, which suffered from a large-scale ransomware campaign that knocked out a number of city services and required tens of millions of dollars to restore the city’s IT networks.

Based on publicly available statistics and announcements monitored by Kaspersky experts, 2019 has seen at least 174 municipal organizations targeted by ransomware. This is an approximately 60% increase from the number of cities and towns that reported falling victim to attacks a year earlier. Whereas not everyone has confirmed the amount of extorted funds and whether a ransom was paid or not, the average demand for ransom ranged from $5,000 to $5,000,000, and on average was equal to around $1,032,460. The numbers, however, varied greatly, as the funds extorted from small town school districts, for example, were sometimes 20 times smaller than those extorted from city halls in big municipalities.

However, the actual damage caused by attacks, according to estimates by independent analysts, often differs from the sum that the criminals request. First of all, some municipal institutions and vendors are insured against cyber-incidents, which compensates the costs one way or another. Secondly, the attacks can often be neutralized by timely incident response. Last but not the least, not all cities pay the ransom: in the Baltimore encryption case, where officials refused to pay the ransom, the city ended up spending $18 million to restore its IT infrastructure. While this sum might seem way more than the initial $114,000 requested by the criminals, paying the ransom is a short-term solution that encourages threat actors to continue their malicious practices. You need to keep in mind that once a city’s IT infrastructure has been compromised, it requires an audit and a thorough incident investigation to prevent similar incidents from occurring again, plus the additional cost of implementing robust security solutions.

Attack scenarios vary. For instance, an attack may be the result of unprotected remote access. In general, however, there are two entry points through which a municipality can be attacked: social engineering and a breach in un-updated software. A vivid illustration of the latter problem has been observed quarterly by Kaspersky experts: the all-time leader of almost all rankings of ransomware most frequently blocked on user devices is WannaCry. Even though Microsoft released a patch for its Windows operating system that closed the relevant vulnerability months before the attacks started, WannaCry still affected hundreds of thousands of devices around the globe. And what’s more striking is the fact that it still lives and prospers. The latest statistics gathered by Kaspersky in Q3 2019 demonstrated that two and a half years after the WannaCry epidemic ended, a fifth of all users targeted by cryptors were attacked by WannaCry. What’s more, the statistics from 2017 to mid-2019 show that WannaCry is consistently one of the most popular malware samples, accounting for 27% of all users attacked by ransomware in that time period.

An alternative scenario involves criminals exploiting human factors: this is arguably the most underestimated attack vector, as training of employees in security hygiene is nowhere near as universal as it should be. Many industries lose a tremendous amount of money due to employee errors (in some industries this is the case for half of all incidents), phishing and spam messages containing installers for dangerous malware are still circulating around the web and reaching victims. Sometimes those victims may be managing the company’s accounts and finances and not even suspect that opening a scammer email and downloading what appears to be a PDF file on their computers can result in a network being compromised.

Among the many types of municipal organizations attacked throughout 2019, some attracted more attacks than others.

The most targeted entities were undoubtedly educational organisations, such as school districts, accounting for approximately 61% of all attacks: 2019 saw operations against more than 105 school districts, with a whopping 530 schools targeted. This sector has been hit hard, yet demonstrated a resilience: while some colleges had to cancel classes, many educational institutions adopted a position of continuing studies despite a lack of technical support, claiming that computers have only recently become part of the educational process, and that staff are perfectly capable of teaching pupils without them.

City halls and municipal centers, meanwhile, accounted for around 29% of cases. Threat actors are often aiming at the heart of processes that, if stopped, will result in an extremely problematic interruption of vital processes for the vast majority of citizens and local organizations. Unfortunately, such institutions are still often equipped with weak infrastructure and unreliable security solutions, as the workflow (especially in small, quiet towns or villages without advanced infrastructure) does not require high computing capacities. As a consequence, the locals often don’t bother updating old computers because they appear to still be functioning well. This might be related to a common mistake, whereby security updates are associated with design changes or technical developments introduced in the software, while their most vital function is in fact closing breaches found by white- or black-hat hackers and security researchers.

Another popular target was hospitals, accounting for 7% of all attacks. While some black-hat hackers and cybercriminal groups claim to have a code of conduct, in most cases attackers are motivated purely by the prospect of financial gain and go for vital services that cannot tolerate long periods of disruption, such as medical centers.

Furthermore, around 2% of all institutions subjected to an attack were municipal utility services or their subcontractors. The reason for this might be that such service providers are often used as an entry point to a whole network of devices and organizations, as they are responsible for communications in terms of billing for multiple locations and households. In the scenario where threat actors successfully attack the service provider, they might also compromise every locality that particular vendor or institution services. In addition, the disruption of utility services may result in disruption to vital regular operations, such as providing online payment services for residents of the town or city to pay their monthly bills – this adds to the pressure the victims’ experience and pushes them towards a short-term, yet seemingly effective solution – paying the ransom.

Let’s take a closer look at the malware that has been actively used in attacks on municipalities.

The besiegers

Ryuk

While not all organizations disclose technical details about the ransomware that hits them, Ryuk ransomware (Detection name: Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Hermez) has been cited as a reason for incidents in municipalities noticeavly often. It is known to be notorious for attacking large organizations and governmental and municipal networks. This malware first appeared in the second half of 2018 and has been mutating and actively propagating throughout 2019.

Geography

(Download)

TOP 10 countries

| Countries | %* | |

| 1 | Germany | 8.60 |

| 2 | China | 7.99 |

| 3 | Algeria | 6.76 |

| 4 | India | 5.84 |

| 5 | Russian Federation | 5.22 |

| 6 | Iran | 5.07 |

| 7 | United States | 4.15 |

| 8 | Kazakhstan | 3.38 |

| 9 | United Arab Emirates | 3.23 |

| 10 | Brazil | 3.07 |

*Percentage of users attacked in each country by Ryuk, relative to all users attacked worldwide by this malware

Ryuk has been seen all over the world, although some countries have been affected more than others. According to Kaspersky Security Network statistics, in 8.6% of cases it attempted to attack German-based targets, followed by China (8%) and Algeria (6.8%).

Distribution

The threat actors behind Ryuk employ a multi-stage scheme to deliver this ransomware to their victims.

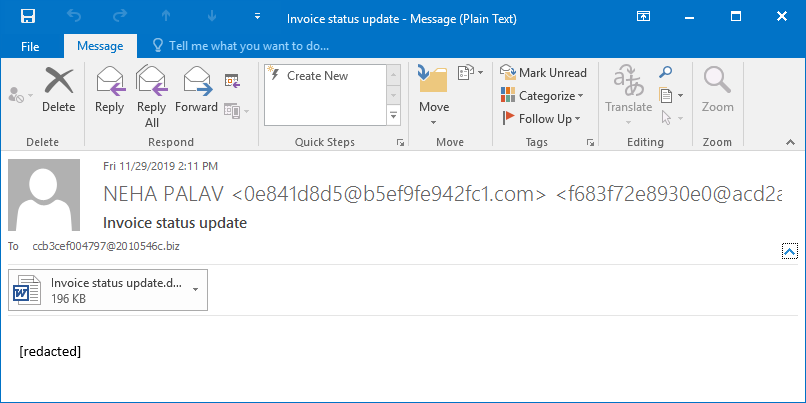

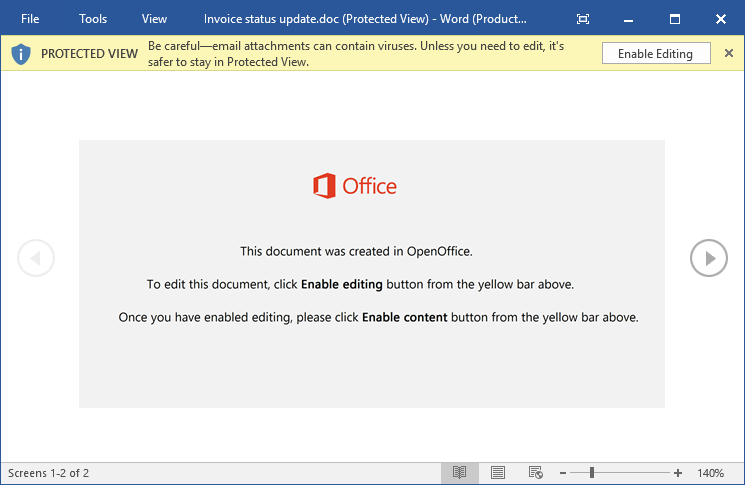

The initial stage involves infecting a large number of machines by the Emotet bot (Detection name: Trojan-Banker.Win32.Emotet). Typically this is achieved by sending out spam emails containing a document with a malicious macro that will download the bot if the victim allows the execution of macros.

Spam message with a malicious document attached

The malicious document

At the second stage of the infection, Emotet will receive a command from its servers to download and install another piece of malware – Trickbot (verdict: Trojan.Win32.Trickster) – into the compromised system. This piece of malware will allow the threat actors to carry out reconnaissance in the compromised network.

If the criminals find they have infiltrated a high-profile victim, for example, a large municipal network, or a corporation, they will likely continue to the third stage of the infection and deploy Ryuk ransomware to numerous nodes in the affected network.

Brief technical description

Ryuk has been evolving since its creation and there is a certain variation between the numerous samples existing ITW. Some of them are built as 32-bit binaries, others are 64-bit; some variants contain a hardcoded list of processes that will be targeted for code injections, other variants allowlist several processes and will try to inject all others; the encryption scheme also sometimes differs from one sample to another.

We will describe one of the recent modifications discovered in late October 2019 (MD5: fe8f2f9ad6789c6dba3d1aa2d3a8e404).

File encryption

This modification of Ryuk uses a hybrid encryption scheme employing the AES algorithm to encrypt the content of the victim’s files, and the RSA algorithm to encrypt the AES keys. Ryuk uses the standard implementation of cryptographic routines provided by Microsoft CryptoAPI.

The Trojan sample contains the threat actor’s embedded 2048-bit RSA key. The private counterpart is not exposed and may be used by the criminals for decryption if the ransom is paid. For each victim file Ryuk will generate a new unique 256-bit AES key that will be used to encrypt the file content. The AES keys are encrypted by RSA and saved at the end of the encrypted file.

Ryuk encrypts both local drives and network shares. Encrypted files will get an additional extension (.RYK), and a ransom note containing the email of the criminals will be saved nearby.

Ransom note

Additional functionality

To cause more damage in the network, this Ryuk variant uses a trick that we haven’t observed in other ransomware families before; the Trojan attempts to wake other machines that are in a sleeping state but have been configured to use Wake-on-LAN.

Ryuk does this in order to maximize the attack surface: the files located on network shares hosted on sleeping PCs are unavailable for access, but if the Trojan manages to wake them, it will be able to encrypt those files as well. To achieve this, Ryuk retrieves the MAC addresses of the nearby machines from the local ARP cache of the infected system and sends broadcast UDP packets starting with the magic value {0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff, 0xff} to port 7 which will wake up the targeted computers.

Fragment of the procedure implementing Wake-on-Lan packet broadcast

Other features of the Ryuk algorithm that are more conventional for ransomware families include: code injection into legitimate processes in order to avoid detection; attempting to terminate processes related to business applications to make the files used by these programs available for modification; attempting to stop various services related both to business applications and to security solutions.

Purga

This ransomware family appeared in the middle of 2016 and is still being actively developed and distributed around the world. It has been recorded targeting municipalities. One of the features of this malware is that it attacks regular users as well as large corporations and even governmental organizations. Our products detect this malware as Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Purga. The Trojan family is also known as Globe, Amnesia or Scarab ransomware.

Geography

(Download)

TOP 10 countries

| Countries | %* | |

| 1 | Russian Federation | 85.59 |

| 2 | Belarus | 1.37 |

| 3 | Turkey | 0.85 |

| 4 | India | 0.80 |

| 5 | Kazakhstan | 0.74 |

| 6 | Germany | 0.62 |

| 7 | Ukraine | 0.54 |

| 8 | China | 0.46 |

| 9 | Algeria | 0.40 |

| 10 | United Arab Emirates | 0.40 |

*Percentage of users attacked in each country by Purga, relative to all users attacked worldwide by this malware

Distribution

Throughout this family’s existence, the criminals behind it have used various types of infection vectors. The main attack vectors are spam campaigns and RDP brute-force attacks.

According to our information, this is currently the most common attack scenario:

- The criminals scan the network to find an open RDP port

- They try to brute-force credentials to log in to the targeted machine

- After a successful login, the criminals try to elevate privileges using various exploits

- The criminals launch the ransomware

Brief technical description

Purga ransomware is an example of very intensively developed ransomware. Over the last couple of years, the criminals have changed several encryption algorithms, key generation functions, cryptographically schemes and so on.

Here we will briefly describe the latest modification.

Naming scheme:

Each modification of Purga uses a different extension for each file and a different email address to contact. Despite using various extensions for the encrypted files, the Trojan uses only two naming schemes, which depend on its configuration:

- [original file name].[original extension].[new extension]

- [encrypted file name].[new extension]

File encryption

During encryption the Trojan uses a standard scheme that combines symmetric and asymmetric algorithms. Each file is encrypted using a randomly generated symmetric key, then this symmetric key is encrypted with an asymmetric key and the result is stored in the file, in a specifically built structure.

Stop

The notorious Stop ransomware (also known as Djvu STOP) was first encountered at the end of the 2018. Our detection name for this family is Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Stop and, according to our statistics, in 2019 alone the various modifications of Stop ransomware attacked more than 20,000 victims around the world. Unsurprisingly, according to our KSN report for the third quarter of 2019, Stop ransomware finished seventh among the most common ransomware.

Geography

(Download)

TOP 10 countries

| Countries | %* | |

| 1 | Vietnam | 10.28 |

| 2 | India | 10.10 |

| 3 | Brazil | 7.90 |

| 4 | Algeria | 5.31 |

| 5 | Egypt | 4.89 |

| 6 | Indonesia | 4.59 |

| 7 | Turkey | 4.30 |

| 8 | Morocco | 2.42 |

| 9 | Bangladesh | 2.25 |

| 10 | Mexico | 2.09 |

*Percentage of unique users attacked in each country by Stop, relative to all users attacked worldwide by this malware

Distribution

The authors chose to distribute their malware primarily through software installers. When users try to download specific software from an untrusted site or try to use software cracks, instead of the desired result their machines become infected by the ransomware.

Brief technical description

For file encryption, Stop ransomware uses a randomly generated Salsa20 key, which is then encrypted by a public RSA key.

Fragment of code from the file encryption routine

Depending on the availability of the C&C server, Stop ransomware uses either an online or offline RSA key. The offline public RSA key can be found in the configuration of each malicious sample.

Dumped fragment of the malware

Conclusion and recommendations

2019 has been a year of ransomware attacks on municipalities, and this trend is likely to continue in 2020. There are various reasons why the number of attacks on municipalities is increasing.

First of all, the cybersecurity budgeting of municipalities is often more focused on insurance and emergency response than on proactive defense measures. This results in cases where the only possible solution is to pay the criminals and facilitate their activities.

Secondly, municipal services often have numerous networks that include multiple organizations, so hitting them causes disruption on many levels at the same time, bringing processes across entire districts to a halt.

What’s more, the data stored in municipal networks is often vital for the functioning of everyday processes, as it directly concerns the welfare of citizens and local organizations. By striking such targets, cybercriminals are hitting a sensitive spot.

However, simple preventive measures can help combat the epidemic:

- It is essential to install all security updates as soon as they appear. Most cyberattacks exploit vulnerabilities that have already been reported and addressed, so installing the latest security updates lowers the chances of an attack.

- Protect remote access to corporate networks by VPN and use secure passwords for domain accounts.

- Always update your operating system to eliminate recent vulnerabilities and use a robust security solution with updated databases.

- Always have fresh back-up copies of your files so you can replace them in case they are lost (e.g. due to malware or a broken device) and store them not only on a physical medium but also in the cloud for greater reliability.

- Remember that ransomware is a criminal offence. You shouldn’t pay a ransom. If you become a victim, report it to your local law enforcement agency. Try to find a decryptor on the internet first – some of them are available for free here: https://noransom.kaspersky.com

- Educating employees about cybersecurity hygiene is necessary to prevent attacks from happening in the first place. Kaspersky Interactive Protection Simulation Games offer a special scenario that focuses on threats relevant to local public administration.

- Use a security solution for organizations in order to protect business data from ransomware. Kaspersky Endpoint Security for Business has behavior detection, anomaly control and exploit prevention capabilities that detect known and unknown threats and prevent malicious activity. A preferred third-party security solution can also be enhanced with the free Kaspersky Anti-Ransomware Tool.

Story of the year 2019: Cities under ransomware siege