- Malware Evolution 2010

- Kaspersky Security Bulletin. Statistics, 2010

- Kaspersky Security Bulletin. Spam Evolution 2010

This is Kaspersky Lab’s annual threat analysis report covering the major issues faced by corporate and individual users alike as a result of malware, potentially harmful programs, crimeware, spam, phishing and other different types of hacker activity.

The report has been prepared by the Global Research & Analysis Team (GReAT) in conjunction with Kaspersky Lab’s Content & Cloud Technology Research and Anti-Malware Research divisions.

2010: The Year of the Vulnerability

The year 2010 has been almost identical to the previous one in terms of malware evolution. Generally speaking, trends have not changed that much and nor have the targets attacked; although a number of the technologies used have progressed dramatically.

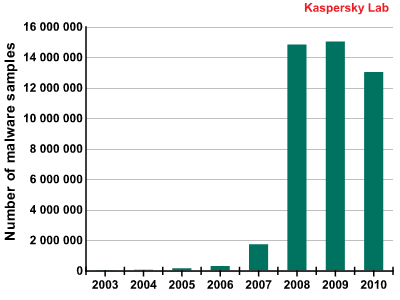

Whilst monthly malware detection rates have remained reasonably stable since 2009, there has been a downturn in the activities of certain types of malware. This trend towards stabilization in the flow of malware was reflected in our 2009 report. The reasons remain unchanged: a downturn in the activity of some Trojans, particularly gaming Trojans, and the efforts of law enforcement agencies, antivirus vendors and telecom providers in clamping down on illegal services and cybercriminal gangs. Another contributing factor has been the relevant stability in the number of malicious programs in circulation and a reduction in the number of Rogue AVs, which we had expected.

Number of malware samples in Kaspersky Lab’s collection

However, the fact that the number of new malicious programs has remained stable does not automatically imply any stabilization in the number of attacks. Firstly, malware is constantly growing more complex, and that is true even from one year to the next. Secondly, cybercriminals attack computers via the many vulnerabilities in browsers and third-party applications that interact with them. As a result, the same malicious program can often be distributed via ten different vulnerabilities, leading to a proportional increase in the number of attacks.

The total number of recorded attacks can be classified according to 4 main types:

- Attacks via the Internet (detected by web antivirus);

- local incidents (detected on user computers);

- network attacks (detected by IDS);

- email incidents.

In 2010, the total number of recorded incidents exceeded 1.5 billion for the first time since we began our observations! Attacks via browsers accounted for over 30% of these incidents, that’s over 500 million blocked attacks. This information will be analyzed in detail in the statistical part of the report.

Vulnerabilities have really come to the fore in 2010. Exploiting vulnerabilities has become the prime method for penetrating users’ computers, with vulnerabilities in Microsoft products rapidly losing ground to those in Adobe and Apple products such as Safari, QuickTime and iTunes. Such attacks are performed using sets of exploits for different vulnerabilities in browsers and plugins for them. Exploits for vulnerabilities in Adobe applications were the absolute 2010 leader in terms of the number of recorded incidents due to vulnerabilities.

While in times gone by the cybercriminals mainly exploited vulnerabilities in the early stages of penetrating a system, in 2010, several malicious programs were detected that exploit different vulnerabilities at all stages of their operation. Some of them, Stuxnet for instance, have also exploited ‘zero-day’ vulnerabilities.

Outcomes for 2010

Many of the forecasts given in our 2009 report were realized in 2010. However, some incidents turned out to be unpleasant surprises for everybody.

As for our forecasts regarding probable trends in the development of cybercrime and types of attacks, most of them proved to be correct.

An increase in the number of attacks via P2P networks (correct)

It is fair to say that P2P networks are now a major channel through which malware penetrates users’ computers. In terms of security incident rates, we estimate this infection vector to be second only to browser attacks.

Practically all types of threats, including file viruses, Rogue AVs, backdoors and various worms spread via P2P-networks. Additionally, such networks have fast become an environment conducive to the propagation of new threats, such as ArchSMS.

The increase in cybercriminal activity on P2P networks has been well documented by other IT companies too. For example, in their Q2-2010 threat report, Cisco stated that the number of attacks carried out via the three most popular P2P networks, BitTorrent, eDonkey and Gnutella, had risen dramatically.

The P2P malware epidemic started in March, when the number of incidents detected by the Kaspersky Security Network exceeded the 2.5 million per month mark for the first time. A conservative estimate of the number of attacks occurring monthly by the end of the year puts the figure at somewhere close to 3.2 million.

It is worth noting that these indicators are only true for malicious programs such as worms which propagate via P2P networks. In addition to these, the number of Trojans and viruses seen in P2P networks is considerable – thus the total number of incidents could be as high as 10 million per month.

Competition for traffic (correct)

So-called partner programs have remained the prime method of cooperation between cybercriminal groups who create new botnets, manage existing ones and decide on new targets for their creations.

2010 saw a whole host of ‘grey’ money-making schemes in operation alongside openly criminal activities, such as infecting legal websites or infecting users’ computers by means of drive-by downloads. Grey schemes include coercing users into voluntarily downloading files by various means, using hijacked resources for Black SEO, distributing attention-grabbing links, spreading adware and redirecting traffic to adult content sites.

To learn more about how such ‘partner programs’ work, please read the article: ‘The Perils of the Internet‘.

Malware epidemics and the increasing complexity of malicious programs (correct)

No epidemics occurred in 2010 that are comparable to the Kido (Conficker) worm epidemic of 2009 in terms of propagation speed, the number of affected users and the scope of attention it attracted. However, if these factors are considered separately, outbreaks of certain infections may be classified as global epidemics.

The Mariposa, ZeuS, Bredolab, TDSS, Koobface, Sinowal and Black Energy 2.0 botnets attracted a lot of attention from both journalists and analysts in 2010. Each attack involved millions of infected computers located all over the world. These threats are among the most advanced and sophisticated malware ever created.

They propagated using all of the existing infection vectors, including regular email. They were the trailblazers in social and P2P networks, and some of them were also the first to infect 64-bit platforms, with many propagating via zero-day vulnerabilities.

The creativity of malware writers peaked with the truly revolutionary Stuxnet worm. To analyze it fully and understand its functionality and the operation of its components, the experts needed over three months. Stuxnet grabbed the cybersecurity headlines in the second half of 2010 and left all previously known malware behind in terms of the number of publications it generated.

We are witnessing an apparent trend in which the most widespread malicious programs tend to be the most sophisticated. This raises the bar for the manufacturers of cybersecurity products who are waging technological warfare on the cybercriminals. These days, it is not enough to be able to identify ninety-nine percent of the millions of malware samples out there, but then fail to detect or treat the one threat which is extremely sophisticated and therefore widespread.

Decreasing numbers of Rogue AVs (correct)

This prediction was fairly controversial – opinions on this issue are divided, even among Kaspersky Lab experts. It depended on a number of additional factors: the owners and participants of partner programs shifting to other methods of making money, counteraction by antivirus companies and law-enforcement agencies, and the presence of serious competition between different cybercriminal groups creating and distributing Rogue AVs.

According to figures for the year garnered from KSN, the number of Rogue AVs has in fact decreased globally. Rogue AV activity peaked at around 200,000 incidents per month in February-March 2010, before experiencing a fourfold decrease towards the end of 2010. At the same time, existing Rogue AVs tended to narrow their target zones to specific regions, with cybercriminals ceasing to spread them indiscriminately and focusing on specific countries such as the USA, France, Germany and Spain.

Attacks on and via Google Wave (incorrect)

A year ago, we predicted that there would be attacks on Google Wave and its clients. However, this project was abandoned by Google around mid-2010, before it gathered a critical mass of users and came into full operation. Thus our prediction did not have a chance to come true.

Attacks on iPhone and Android devices (partially correct)

In 2009, the first iPhone malware and a spyware program for Android were detected. We expected the cybercriminals to focus much more of their attention on these two platforms.

No significant malware events occurred that targeted iPhone and which could be compared to the Ike worm incident of 2009. However, several concept programs were created for this platform in 2010 that demonstrated techniques that could be used by the cybercriminals. A truly remarkable example of one such technique was ‘SpyPhone’, the brainchild of a Swiss researcher. This program allows unauthorized access to information about the user’s iPhone device, his or her location, interests, friends, preferred activities, passwords and web search history. This data can then be sent to a remote server without the user’s knowledge or consent. This functionality can be hidden within an innocuous-looking application.

While in the past, experts have said that users who have jailbroken their iPhones to install third-party applications are increasing the risk to themselves, it is now the case that even those installing native applications downloaded from Apple Store are also exposing themselves to a degree of threat. Several incidents have taken place that involved legitimate Apple applications – iPhone apps were detected that covertly gathered data and sent it to software manufacturers.

Everything mentioned above is also relevant to the Android platform. Malware of an overtly cybercriminal nature has been detected for the Android platform that uses the popular mobile Trojan technique of sending SMSs to premium-rate numbers. Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.FakePlayer was detected by Kaspersky Lab in September 2010, and became the first real example of Android malware – it was apparently created by Russian virus writers. This piece of malware was distributed via malicious websites rather than through Android Market; however, Kaspersky Lab experts believe there is also a strong probability that malware may soon be found in products available through Android Market. We are concerned about the fact that many legitimate applications can ask for, and typically be granted, access to a user’s personal data and authorization to send SMSs and make calls. In our view, this places the reliability of the entire Android security concept in doubt.

That concludes the summary of our predictions and whether they have come true or not. We will continue with a review of certain trends and specific incidents that have had a significant impact on the field of IT security.

Targeted attacks on corporations and industrial enterprises

The attack known as Aurora affected a number of large companies located around the globe, including Google, which was considered its primary target. This incident brought to light serious security breaches and identified the attackers’ potential goals which were cyber-espionage and the theft of confidential commercial data. Future targeted attacks are likely to have similar aims.

The Stuxnet story that we mentioned above is remarkable in two respects. Firstly, its level of sophistication beat all previous records, and secondly, it was designed to specifically target programmable logic controllers (PLCs). PLCs are commercially available industrial control devices that are typically used in industry. To date, this has been the first instance of industrial cyber-sabotage to attract such widespread publicity. Attacks like this can potentially inflict significant physical damage. The boundary between the virtual world and the real world has now become blurred and this poses new problems that the entire cyber-community will have to face in the near future.

Digital certificates

Digital certificates and signatures are one of the pillars upon which confidence and assurance in the computer world are based. Digital signatures naturally play an important role in developing security products: files signed by trusted manufacturers are regarded as clean. This technology helps the manufacturers of cybersecurity products reduce false positive rates and save resources when scanning users’ computers for infection.

The events of 2010 have demonstrated that the cybercriminals are able to obtain digital certificates in a legal manner, just like any software manufacturer does. In one instance, a certificate was obtained for a program which purported to be a piece of ‘software to remotely manage computers that do not have a GUI’, though the program was actually a backdoor. This trick is useful to the cybercriminals as it prevents malware from being detected and is most often used in adware, riskware and Rogue AVs. Having received a certification key, a cybercriminal can easily provide every malicious program that he or she creates with a digital signature.

The whole concept of software certification as a means of ensuring cybersecurity has, in effect, been seriously discredited. In fact, this may have a knock-on effect in that it discredits some of the digital certification centers which at present total some several hundred in number. In the worst case, it could mean the emergence of certification centers controlled by the cybercriminals themselves.

A digital certificate, or technically, the privacy key contained within it, is a physical file that can potentially be stolen just like any other digital asset. The Stuxnet components that were detected were signed with certificates issued to Realtec Semiconductors and JMicron. It remains unclear exactly how a privacy key fell into the hands of cybercriminals, though there are a number of ways it could have happened. They may have acquired these confidential files by illicitly purchasing them from insiders, or stealing them using some type of backdoor or similar piece of malware. For example, the ability to steal certificates appears to be something that the ubiquitous Zbot, or ZeuS as it is otherwise known, would be capable of.

Major incidents and events of the year

Aurora

The Aurora attack that occurred in early 2010 and was the focus of much attention from both security experts and the media. It affected a number of large companies, including Google and Adobe. Apart from users’ confidential information, the cybercriminals behind the attack also planned to get hold of the codes belonging to a number of corporate projects.

The attack exploited the CVE-2010-0249 vulnerability in Internet Explorer. At the time the cybercriminals used it, Microsoft hadn’t released a patch for it. Aurora is therefore yet another shining example of exploiting a zero-day vulnerability.

Trojans designed to extort

At the beginning and middle of 2010, users in Russia and some of the former Soviet republics were confronted with a wave of infections caused by different variants of so-called SMS blockers – one of the dominant malware threats of that period.

When launched on a victim computer, the malware, which used a variety of methods to spread including popular Russian social networks, drive-by downloads and peer-to-peer networks, blocked the victim machine’s operating system or Internet access and demanded that the user send an SMS message to a premium-rate number in order to receive an ‘unblock code’.

The scale of the problem turned out to be so great and the number of victims so significant that it prompted law enforcement agencies to become involved and gained extensive Russian media coverage, from television to the blogosphere. Mobile phone operators did what they could to combat the threat by introducing new rules for registering and operating premium-rate (short) numbers, blocking accounts that had been used to perpetrate fraud and informing their customers about this type of SMS fraud.

In late August, several people were arrested in Moscow and accused of creating SMS blockers. According to the Russian Ministry of the Interior, the illegal income generated by that criminal group is estimated at 500 million rubles (about 12.5 million euros).

However, the problem is not about to go away. Cybercriminals now simply use other methods to receive payments for ‘unblocking’ their victims’ computers, for example, via electronic money systems or payment terminals.

In addition, new incidents involving encryption Trojans similar to Gpcode were recorded towards the end of the year. These Trojans encrypt data using strong encryption algorithms such as RSA and AES, and then demand payments for restoring the data.

Stuxnet

In terms of its effect on the industry, the detection of the Stuxnet worm in summer 2010 turned out to be the most significant event of the year – and not just that year. A cursory look at the worm revealed two major factors that made more detailed analysis absolutely imperative.

The first factor was that it was clear from the start that the malware exploits a Windows zero-day vulnerability related to the incorrect parsing of LNK files (CVE-2010-2568). The vulnerability is exploited in order to launch malicious files from removable USB drives. It quickly caught the attention of other cybercriminals too: malicious programs that also exploit this vulnerability were detected as early as July. More specifically, we have seen exploits for this vulnerability used to spread Sality and Zbot (ZeuS). In the third quarter alone, 6% of KSN users experienced attacks involving exploits for the CVE-2010-2568 vulnerability.

The second factor was that the worm used legitimate digital certificates issued to Realtek. We mentioned this issue in the Digital certificates section above.

Additionally, one of Stuxnet’s malicious components signed with a JMicron certificate was detected too, but nobody ever traced the original carrier file, or ‘dropper’ that installed the component. The origin of the component is another blank spot in the history of Stuxnet, which is in any case, remarkably mysterious.

Further analysis of the worm produced three more Windows zero-day exploits. One was responsible for spreading the worm over local area networks and took advantage of a vulnerability in the Windows printer sharing service. The vulnerability was discovered by Kaspersky Lab experts and Microsoft released a patch for it in September 2010. Two more vulnerabilities – in the win32k.sys component and the Task Scheduler – were exploited to elevate the worm’s privileges. Kaspersky Lab experts were also instrumental in discovering the first of these two vulnerabilities.

However, although Stuxnet exploits five vulnerabilities and also uses a vulnerability in Siemens WinCC software connected with default access passwords, exploiting vulnerabilities is not the most remarkable of the worm’s properties. The malware targets systems that have a certain configuration of SIMATIC WinCC/PCS7, which, and this is the crux, attacks specific models of programmable logic controllers (PLC) and frequency converters from specific manufacturers. A dynamic-link library installed by the worm hooks some of the system functions and can therefore affect the running of control systems that manage the operation of certain industrial facilities. The worm’s principal purpose is to interfere with the logic of controllers used by frequency converters. These controllers are used to adjust the rotation frequency of very high-speed motors that have an extremely limited range of applications – one example being to drive centrifuges.

TDSS

TDSS stood out clearly among ‘conventional’ malware in 2010. We use the word ‘conventional’ here due to the emergence of Stuxnet (see above), which undoubtedly represents a completely new phenomenon on the malware scene and simply could not have been produced by cybercriminals of average ability.

The TDSS backdoor was the subject of many of our analytical publications in 2009-2010. Experts from other antivirus vendors showed a similar level of interest. This is easy to explain: with the exception of Stuxnet, TDSS is the most sophisticated piece of malicious code seen to date. Not only is it constantly being updated to include new methods of masking its presence in the system, its authors also make a point of exploiting a variety of vulnerabilities, both zero-day and those for which patches have been released.

The most significant enhancement to TDSS in 2010 was implementation of 64-bit operating system support. That modification was detected in August and had the internal number TDL-4. To evade the protection system built into Windows, TDSS authors used an MBR infection technique similar to that used in another Trojan – Sinowal. If MBR is successfully infected, malicious code starts executing even before the operating system starts. It can then modify the startup parameters in such a way that unsigned drivers can be registered in the system.

The rootkit loader detects the type of system – 32- or 64-bit – in which the malware is going to operate, reads the driver’s code into memory and registers the driver in the system. Following this, the operating system is started, with the malicious code already injected. Importantly, the rootkit does not modify the kernel structures that are protected by PatchGuard, another technology built into the operating system.

Microsoft, when informed about the problem identified by Kaspersky Lab’s experts, did not regard the issue as critical and declined to classify it as a vulnerability, since the Trojan must already have administrator privileges to write its code to MBR.

TDSS uses a constantly enhanced range of tricks to gain such privileges. In early December we discovered that TDSS uses an additional zero-day vulnerability to elevate its privileges – a Task Scheduler vulnerability that was first exploited by Stuxnet and that was only closed by Microsoft in the middle of December 2010.

Numerous Twitter and Facebook incidents

Two of the most popular and rapidly expanding social networks were targeted by numerous attacks in 2010. Social networks have become a medium for malware distribution, helped by the discovery of vulnerabilities in these networks, which make the task easier to achieve.

Among malicious programs, numerous variants of the Koobface worm were the most active. They mostly targeted Twitter, whose compromised accounts were then used to distribute links to Trojans. How effective distribution via social networks can be is demonstrated by the following statistic: in just one minor Twitter attack, a malicious link was followed by over 2,000 users in one hour.

A revealing situation linked to the popularity of the iPhone took place on Twitter in May. On 19 May, Twitter’s administration team made an official announcement that a new application, ‘Twitter for iPhone’, had been released. Cybercriminals decided to ride the wave of discussion caused by the announcement. Less than an hour after the new application was announced, Twitter was awash with messages that included the words ‘twitter iPhone application’, with links leading to Worm.Win32.VBNA.b.

In addition, some malware writers used Twitter to generate new domain names for botnet command-and-control centers.

Cybercriminals actively exploited the several XSS vulnerabilities found in Twitter in 2010. Attacks carried out in September were particularly notable. They involved infesting the social network with several XSS worms that could spread without user interaction: it was sufficient just to view an infected message. According to our estimates, over half a million Twitter users were attacked during these outbreaks.

A new type of attack appeared on Facebook in May. It was based on the newly-introduced ‘Like’ feature. As can be easily guessed, the feature creates a list of things that an owner of a Facebook account likes. Thousands of users fell victim to the attack which was dubbed ‘Likejacking’, a play on the term ‘Clickjacking’.

The attack involved placing an enticing link on Facebook, e.g., ‘World Cup 2010 in HD’ or ‘101 Hottest Women in the World’. The link led to a specially created page, where JavaScript code placed an invisible ‘Like’ button wherever the cursor happened to be. The button kept following the cursor and registered each press regardless of where the user actually clicked. As a result, a copy of the link was added to the user’s Wall and information that the user liked the link appeared on his or her friends’ feeds. The attack had a snowball effect: the link was followed by friends, then friends of friends and so forth. Once the link was added to the Wall, the user was redirected to a page which contained the information advertised, such as pictures of girls. The attack was used for fraudulent purposes: the page also hosted a small piece of JavaScript code for an advertising campaign that provided the cybercriminals who had set up the fraudulent scheme with a small sum every time a user was redirected to the page.

Cybercriminal arrests and botnet shutdowns

In 2008-2009, measures taken against criminal Internet hosting companies and services by law enforcement and other agencies, telecoms providers and the antivirus industry brought some successes. The first step was taken in 2008 when services such as McColo, Atrivo and EstDomains were closed down. In 2009, further steps were taken, resulting in UkrTeleGroup, RealHost and 3FN being forced to cease their activities.

The year 2010 has been the most successful to date for law enforcement agencies in their struggle against cybercrime. We have already mentioned the arrests of several SMS blocker authors in Russia, and this was only a small part of a global campaign to bring cybercriminals to justice.

In early 2010, some of the command servers used by a botnet built by Email-worm.Win32.Iksmas, a.k.a. Waledac, were taken down. The botnet was notorious for large-scale spam attacks, with up to 1.5 billion spam messages sent every day that used enticing material to trick unwary users into clicking on links to, among other malware, Iksmas. The malware used server-side polymorphism of the bot based on fast-flux technology.

In summer, Spanish police arrested the owners of one of the largest botnets Mariposa. The botnet was created using P2P-worm.Win32.Palevo. The worm spreads via peer-to-peer networks, instant messengers and the autorun function which launches executables located on any portable device such as digital cameras or a USB flash drives. The main method of ‘monetizing’ Palevo was selling and using the confidential user data gathered from compromised machines, specifically logins and passwords for online banking and various other services. Later, four young people were arrested in Slovenia and accused of creating the worm’s malicious code to order for Spanish ‘customers’. According to estimates provided by experts, the size of the Mariposa botnet could have reached 12 million machines, placing it among the largest in the history of the Internet.

A member of the so-called ‘RBS hack’ gang was arrested in spring 2010 and convicted in September. The story of cybercriminals stealing over US $9 million from hundreds of ATMs across the globe was extensively covered by the media in 2009. Despite the gravity of the crime and the large amount stolen, a St. Petersburg court sentenced the perpetrator to 6 years probation. Another member of the gang was arrested in Estonia and extradited to the US, where he is currently awaiting trial. Two more gang members have been arrested, one in France, the other in Russia.

The autumn saw mass arrests of criminals associated with ZeuS malware. Twenty people from Russia, the Ukraine and other Eastern European countries were arrested in the US in late September. These were money mules involved in laundering the money stolen with the help of the Trojan. A group of people were also arrested in the UK at the same time on similar charges.

Soon after these events, the supposed author of ZeuS announced on a number of forums frequented by Russian-speaking cybercriminals that he was “getting out of the business” and handing over the Trojan’s source code and its modules to another developer.

In mid-October, the curtain came down on another infamous botnet, this time created using the Bredolab Trojan. In reality, there were several botnets rather than just the one, controlled from more than a hundred command servers. They were all taken offline as a result of an operation conducted jointly by Internet Crime divisions of the Dutch and French police. At the time of its closure, the botnet’s largest branch numbered over 150,000 infected machines. It turned out that the botnet was owned by an Armenian citizen. He had been under police surveillance for several months and was arrested at Yerevan airport upon arrival from Moscow after the servers had been shut down. It is believed that he was involved in illegal deals with other cybercriminals in Russia. There is evidence that he had been involved in cybercrime for over 10 years and was responsible for a number of large-scale DDoS attacks and spam mailings. Another source of his illegal income was renting out or selling parts of the botnet to other criminals.

Forecast for 2011

Cyber Attacks 2011: Steal Everything

In order to better understand what awaits us in 2011 in the field of IT threats, we first need to divide the potential trends into three distinct categories. In this forecast, we will analyze the aims of cyber attacks, look at the methods used to carry them out and examine who the organizers of such attacks are.

In previous forecasts we have only ever looked at the methods used, e.g. attacks on mobile platforms, the exploitation of vulnerabilities, etc. This was because, for the past few years, the perpetrators have always been cybercriminals, and their aims have invariably been financial gain.

However, we may witness a significant sea-change in 2011, with a major shift in the makeup of the organizers and their aims. These changes will be on a par with the demise of malware written by the so-called ‘script kiddies’, whose aim was primarily to show off their virus writing skills, and whose efforts heralded the age of the cybercriminal.

Methods

It’s important to point out that the method used to launch a cyber attack does not depend on who organizes it or what their aims are; instead it’s determined by the technical possibilities presented by today’s operating systems, the Internet and its services, not to mention the devices people use for work and in other areas of their daily lives.

It could be said that 2010 was the ‘Year of the Vulnerability’, and 2011 only promises worse to come. The rise in malicious exploits that seize on programming errors won’t just be down to new vulnerabilities appearing in popular solutions from the likes of Microsoft, Adobe and Apple, but will also occur because of the speed at which cybercriminals react to such loopholes. A couple of years ago the use of a zero-day vulnerability was considered something to write home about, whereas in 2010, they became a common occurrence. Sadly, that trend is set to continue, with zero-day threats becoming even more prevalent. Moreover, the remote code execution class of vulnerabilities will not be the exclusive weapon of choice in 2011, as vulnerabilities that allow privilege escalation, data manipulation and security mechanisms to be bypassed emerge from the shadows to take centre-stage.

The theft of online banking credentials, spam, DDoS attacks, extortion and scams are likely to remain the primary sources of the cybercriminals’ illegal income. Of course, there will be more emphasis placed on some of these methods than on others, but it’s safe to assume that they will all continue to be used to achieve the goals of the cybercriminals in one form or another.

There is little doubt that there will be an increase in the number of threats targeting 64-bit platforms. There will be new developments with regards to attacks on mobile devices and mobile operating systems, and these are likely to affect Android in particular. Attacks on users of social networks will increase. The majority of attacks will make use of vulnerabilities and will be carried out via browsers. DDoS attacks will remain one of the biggest problems plaguing the Internet.

But all of the above are only the entrees to the main course, which will consist of the biggest shift in the threat landscape to date – the emergence of a new breed of organizers with new and more potent aims for their cyber attacks.

New organizers with new aims

As we have already discussed, over the last few years we have grown accustomed to combating malicious code created by cybercriminals for financial gain. The creation of the Stuxnet worm was a significant and frightening departure from the familiar, suggesting a moral and technological barrier had been breached. The attack was an impressive demonstration to the whole world of just what the cybercriminals’ arsenals contain, as well as a wake-up call to the IT security industry because of how difficult it was to counteract. It is even quite possible that programs like Stuxnet could be used as a medium for the know-how and capabilities of secret services and commercial organizations.

Of course, compared to the number of more traditional cybercriminal attacks that will occur, those with Stuxnet’s level of sophistication will be few and far between. However, when they do, they will be potentially far harder to detect and as they are unlikely to affect the average user, only the odd episode will hit the headlines. The majority of victims are unlikely to ever know they have been targeted. The principal aim of such attacks will not be sabotage, as was the case with Stuxnet, but the theft of information.

These types of attacks may only begin in 2011 and come to fruition years later. However, it is already clear that the arrival of this new generation of cybercriminals means that those tasked with counteracting such cyber threats will need to raise their game considerably.

Spyware 2.0

A few years back we outlined the concept of Malware 2.0. Well, now it’s time for another one – Spyware 2.0.

When you look at modern malware it becomes clear that, apart from sending spam and organizing DDoS attacks, its main focus is stealing users’ accounts, regardless of whether they are of the banking, email or social networking variety. In 2011, we expect a new class of spyware programs to emerge, the aim of which can be defined quite simply as: steal everything. They will gather any information that they can about the user: his or her location, work, friends, income, family, hair and eye color, etc. Such a program will leave no stone unturned, examining every document and every photo stored on an infected computer that it can.

This all sounds very much like the sort of data that social networks and Internet advertisers want to get their hands on. In fact, there are plenty of potential buyers out there for this kind of stuff. What they intend to do with the information once they have it doesn’t really matter either. The main thing is that there is a demand for it, and that means it’s a potential goldmine for the switched-on cybercriminal.

They will get in on the act at the earliest opportunity, stealing everything they can get. Information is the most valuable asset in the modern world, because as the saying goes, knowledge is power, and power means control. As a result, the sphere of interest of those who initiate attacks of this type has widened considerably.

Furthermore, traditional cybercrime is increasingly encroaching on those areas that it has, until now, avoided – targeted attacks on businesses. Attacks used to be confined to stealing money from specific users, banking institutions and payment systems; now the technology used by the cybercriminals has advanced to such a degree that they are capable of carrying out industrial espionage, blackmail and extortion.

What to watch in 2011:

- A whole new generation of more organized and more malevolent malware writers

- Malware attacks targeting information as well as for financial gain

- Information becoming the target of the new breed of cybercriminals and another source of income for those already in the game

- The emergence of Spyware 2.0, a new class of malware that steals users’ personal data (identity theft) plus any other type of data it can find

- Spyware 2.0 becoming a popular tool for both new and old players alike

- An increasing number of attacks on corporate users by traditional cybercriminals and the gradual decline in direct attacks on everyday users

- Vulnerabilities remaining the principal method of carrying out attacks and a significant increase in the scope and speed with which they are used.

The content of this document reflects Kaspersky Lab’s view of events at the time of publication and is provided solely for information purposes. Any information contained herein, including URLs and other links to websites, may be modified without prior notice by the document’s owner. Kaspersky Lab ZAO does not guarantee the accuracy of any information provided herein after the date of publication. This information should not be construed as any kind of obligation on the part of Kaspersky Lab ZAO.

Kaspersky Security Bulletin. Malware Evolution 2010