Introduction

Zanubis is a banking Trojan for Android that emerged in mid-2022. Since its inception, it has targeted banks and financial entities in Peru, before expanding its objectives to virtual cards and crypto wallets.

The main infection vector of Zanubis is impersonating legitimate Peruvian Android applications and then misleading the user into enabling the accessibility permissions. Once these permissions are granted, the malware gains extensive capabilities that allow its operators to steal the user’s banking data and credentials, as well as perform remote actions and control the device without the user’s knowledge.

This Android malware is undergoing continuous development, and we have seen new samples extending their data exfiltration and remote-control functionality as well as new obfuscation methods and deceptive tactics. The threat actors behind Zanubis continue to refine its code – adding features, switching between encryption algorithms, shifting targets, and tweaking social engineering techniques to accelerate infection rates. These updates are often aligned with recurring campaigns, suggesting a deliberate effort to keep the malware relevant and effective.

To understand how the Trojan reached its current stage, we need to look back at its origins and the early signs of what was to come. Join us in this blogpost as we take a closer look at the malware’s evolution over time.

2022: From zero to threat

Zanubis was first observed in the wild around August 2022, initially targeting financial institutions and cryptocurrency exchange users in Peru. At the time of its discovery, the malware was distributed through apps disguised as a PDF reader, using the logo of a well-known application to appear legitimate and lure victims into installing it.

In its early stages, Zanubis used to employ a much simpler and more limited approach compared to the functionality we would explore later. The malware retrieved its configuration and the package names of all the targeted applications by reaching a hardcoded pastebin site and parsing its data in XML/HTML format.

Upon startup, the malware would collect key information from the infected device. This included the contact list, the list of installed applications, and various device identifiers, such as the manufacturer, model, and fingerprint. The Trojan also performed specific checks to identify whether the device was a Motorola, Samsung, or Huawei, suggesting tailored behavior or targeting based on brand.

Additionally, the malware attempted to collect and bypass battery optimization settings, likely to ensure it could continue running in the background without interruption. All of the gathered information was then formatted and transmitted to a remote server using the WebSocket protocol. For that, Zanubis used a hardcoded initial URL to establish communication and exfiltrate the collected data and also received a small set of commands from the C2 server.

The malware operated as an overlay-based banking Trojan that abused Android’s accessibility service. By leveraging accessibility permissions, the malware was able to run silently in the background, monitoring which applications were currently active on the device. When it detected that a targeted application was opened, it immediately displayed a pre-generated overlay designed to mimic the legitimate interface. This overlay captured the user’s credentials as they were entered, effectively stealing sensitive information without raising suspicion.

Zanubis targeted 40 banking and financial applications in Peru. The malware maintained a predefined list of package names corresponding to these institutions, and used this list to trigger overlay attacks. This targeting strategy reflected a focused campaign aimed at compromising users of financial services through credential theft.

At that point, the malware appeared to be under active development – code obfuscation had not yet been implemented, making the samples fully readable upon decompilation. Additionally, several debugging functions were still present in the versions captured in the wild.

2023: Multi-feature upgrade

In April 2023, we identified a new campaign featuring a revamped version of Zanubis. This time, the malicious package masqueraded as the official Android application of SUNAT (Superintendencia Nacional de Aduanas y de Administración Tributaria), Peru’s national tax and customs authority. It copied both the name and icon of the legitimate app, making it appear authentic to unsuspecting users.

Shift to obfuscation

Unlike earlier versions, this variant introduced significant changes in terms of stealth. The code was fully obfuscated, making manual analysis and detection more difficult. After decompilation, it became clear that in order to sophisticate the malware analysis, the threat actors used Obfuscapk, a widely used obfuscation framework for Android APKs. Obfuscapk combines multiple techniques, including a range of obfuscators and so-called “confusers”. These techniques vary in complexity: from basic measures like renaming classes, adding junk code, and replacing method signatures, to more advanced strategies such as code RC4 encryption and control-flow obfuscation. The goal was to hinder reverse engineering and slow down both static and dynamic analysis, giving the operators more time to execute their campaigns undetected.

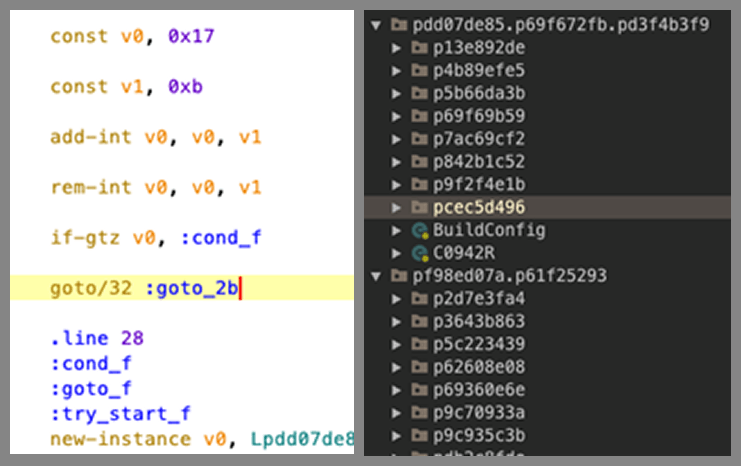

Junk code (on the left) and renaming (on the right) obfuscation methods applied to the malicious implant

Once installed and executed, the malware began setting up its internal components, including various classes, functions, and the SharedPreferences object, which are essential for the Trojan’s operation. The latter typically stores sensitive configuration data such as C2 server URLs, encryption keys, API endpoints, and communication ports.

Deceptive tricks

Throughout all versions of Zanubis, a key step in its execution flow has been to ensure it has accessibility service permissions, which are crucial for its overlay attacks and background monitoring. To obtain these, the malware checks if it is running for the first time and whether the necessary permissions have been granted. If not, it employs a deceptive tactic to manipulate the user into enabling them, a feature that varies between versions.

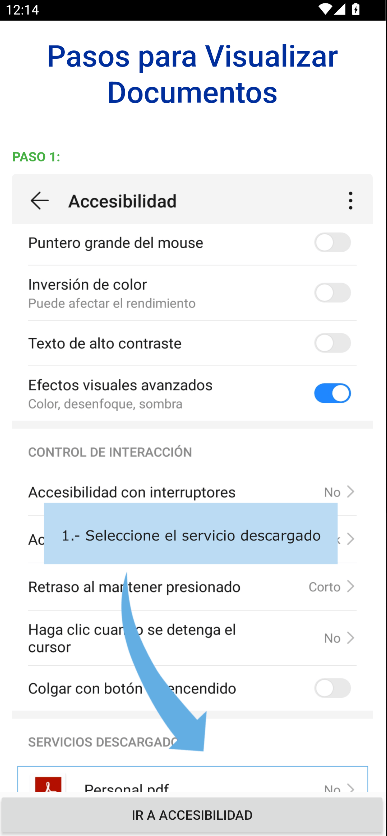

In the 2023 version, the malware displayed a fake instructional webpage using WebView, claiming that additional permissions were needed to view a document – a plausible excuse, given the app’s disguise as an official application. On this page, a prominent button labeled “Ir a Accesibilidad” (“Go to Accessibility”) was presented. Once tapped, the button triggered a redirection to the system’s Accessibility Settings screen or directly to the specific panel for enabling accessibility features for the malicious app, depending on the device model.

Translation:

“Steps to view documents”, “1. Select the downloaded file”.

This trick relies heavily on social engineering, leveraging trust in the app’s appearance and the user’s lack of awareness about Android’s permission system. Once accessibility permissions are granted, the malware silently enables additional settings to bypass battery optimization, ensuring it can remain active in the background indefinitely, ready to execute its malicious functions without user intervention.

With background access secured, the malware loads a legitimate SUNAT website used by real users to check debts and tax information. By embedding this trusted page in a WebView, the app reinforces its disguise and avoids raising suspicion, appearing as a normal, functional part of SUNAT’s official services while continuing its malicious activity in the background.

Data harvesting

Just like earlier versions, the malware began by collecting device information and connecting to its C2 server to await further instructions. Communication with the C2 API was encrypted with RC4 using a hardcoded key and Base64-encoded. Once initialization was complete, the malware entered a Socket.IO polling loop, sleeping for 10 seconds between checks for incoming events emitted by the C2 server. This time, however, the list of available commands had grown significantly, expanding the malware’s capabilities far beyond previous versions.

When a targeted app was detected running on the device, this version of Zanubis took one of two actions to steal user data, depending on its current settings. The first method involved keylogging by tracking user interface events such as taps, focus changes, and text input, effectively capturing sensitive information like credentials or personal data. These logs were stored locally and later sent to the C2 server upon request. Alternatively, Zanubis could activate screen recording to capture everything the user did within the app, sending both visuals and interaction data directly to the server.

SMS hijacking

Another new feature introduced in this campaign is SMS hijacking, a critical technique for compromising bank accounts and services that rely on SMS for two-factor authentication. Once instructed by the C2 server, Zanubis set itself as the default SMS app on the device, allowing it to intercept all incoming messages via a custom receiver. This gave the malware access to verification codes sent by banks and other sensitive services, and even the ability to delete them before the user could see them, effectively hiding its activity.

These actions remained completely hidden from the user. Even if the user attempted to regain control and set their default SMS app back to normal, Zanubis would block that possibility.

Fake updates

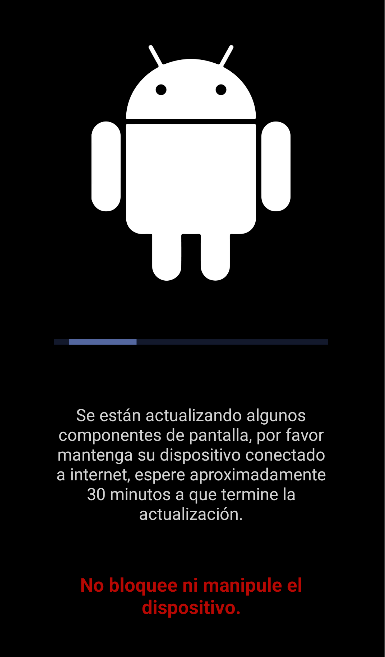

One of the most invasive and deceptive behaviors exhibited by Zanubis was triggered through the bloqueoUpdate (“update lockout” in English) event, which simulated a legitimate Android system update. When activated, the malware locked the device and prevented any normal interaction, rendering it almost completely unusable. Attempts to lock or unlock the screen were detected and locked, making it nearly impossible for the user to interrupt the process.

Before displaying the fake update overlay, the malware could send a warning notification claiming that an urgent update was about to be installed, advising the user not to interact with the device. This increased the credibility of the ruse and reduced the chances of user interference.

Behind this fake update, Zanubis continued operating silently in the background, performing malicious tasks such as uninstalling apps, intercepting SMS messages, changing system settings, and modifying permissions, all without the victim’s awareness.

Translation:

“Some screen components are being updated, please keep your device connected to the internet and wait approximately 30 minutes for the update to finish”. “Do not lock or interact with the device”.

2024: Continuous development

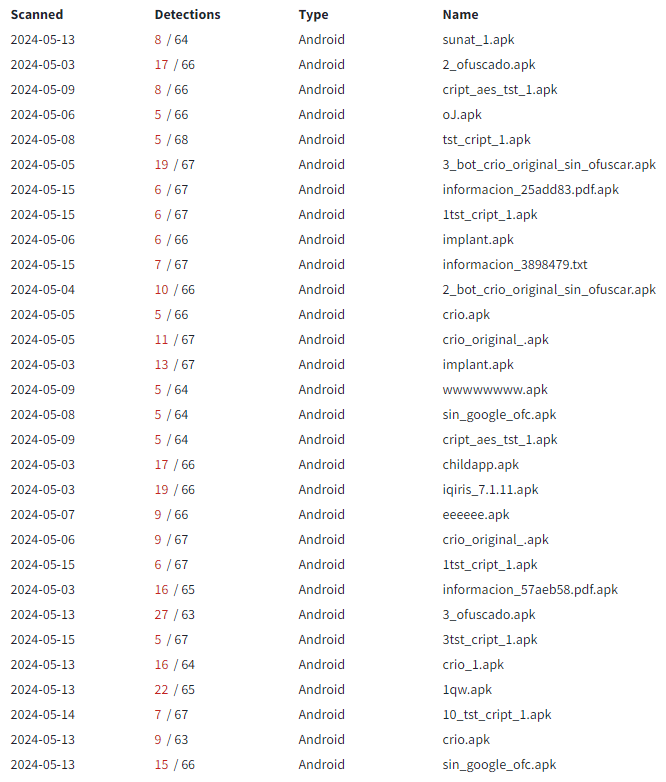

During 2024, we continued monitoring Zanubis on various resources, including third-party platforms. In early May, we detected the appearance of new variants in the wild, particularly observed on VirusTotal. Over 30 versions of the malware were uploaded from Peru, revealing the developer’s efforts to test and implement new functionalities and features into the malware.

Reinforced encryption

In these newer iterations of Zanubis, the developers implemented mechanisms to protect hardcoded strings, aiming to complicate analysis and reduce detection rates. The threat actors used a key derived via PBKDF2 to encrypt and decrypt strings on-the-fly, relying on AES in ECB mode. This method allowed the implant to keep critical strings hidden during static analysis, only revealing them when needed during execution.

Source strings were not the only data encrypted in these new implants. The communication between the C2 and the malware was also protected using AES in ECB mode, which indicates a shift from the use of RC4 in previous samples. Unlike the hardcoded key used for string encryption, in this case, a new 32-byte key was randomly generated each time data was about to be sent.

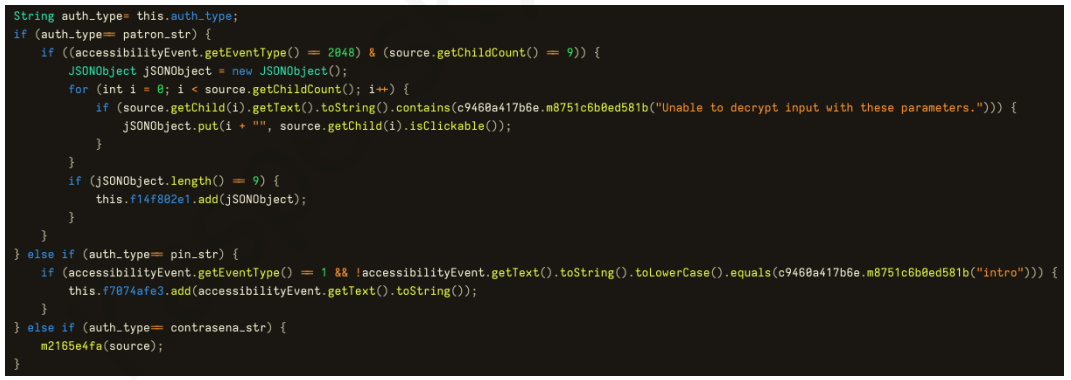

Device credential stealing

Among the most critical actions performed by this version of Zanubis was the theft of device credentials. Once active in the background, the malware constantly monitored system events triggered by other applications. When it detected activity related to authentication that needed the input of a PIN, password, or pattern, it attempted to identify the type of authentication being used and captured the corresponding input.

The malware monitored specific signals that indicated the user was interacting with the lock screen or a secure input method. When these were identified, the malware actively collected the characters entered or gestures used. If it detected that the input was invalid, it reset the authentication tracking to avoid storing invalid data. Once the input process was completed and the user moved on, the malware sent the collected credentials to the C2 server.

Expanding scope

This version of the malware continued to target banking applications and financial institutions in Peru, expanding its reach to include virtual card providers, as well as digital and cryptocurrency wallets. This update added 14 new targeted applications, increasing the scope of its attacks and broadening the range of financial services it can exploit.

2025: Latest campaign

In mid-January of 2025, we identified new samples indicating an updated version of Zanubis. The updates range from changes in the malware distribution and deception strategy to code modifications, new C2 commands, and improved filtering of target applications for credential theft.

New distribution tactics

Zanubis previously impersonated Peru’s tax authority, SUNAT. However, in this new campaign, we have identified two new Peruvian entities being spoofed: a company in the energy sector and a bank that was not previously abused.

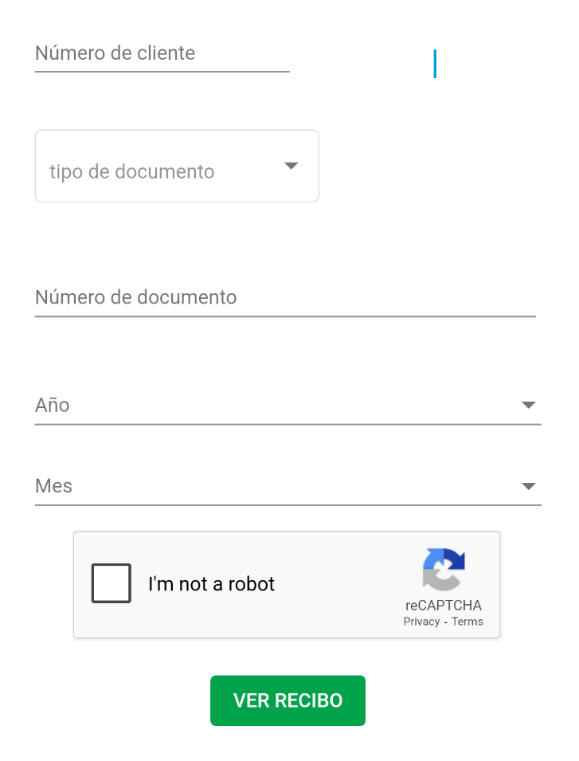

The Trojan initially disguises itself as two legitimate apps from the targeted companies, each crafted to exploit a specific user need. For the energy company, the malicious APK is distributed under names like “Boleta_XXXXXX” (“bill”) or “Factura_XXXXXX” (“invoice”), deceiving users into believing they are verifying a supposed bill or invoice.

Meanwhile, for the bank, victims are enticed to download the malware under the guise of instructions from a fake bank advisor. This setup acts as the initial dropper for the malware, using familiar, trusted contexts to ensure successful installation.

Silent installation

Once the user downloads and launches the lure app, a screen appears with the company’s logo, stating that necessary checks are in progress. Meanwhile, in the background, the dropper attempts to silently install the final payload, Zanubis, which is embedded in the initial malware’s internal resources (res/raw/). To retrieve the APK, the dropper leverages the PackageInstaller class. This installation process occurs without any user involvement, as there are no prompts or warnings to alert the victim. By utilizing PackageInstaller, the malware writes the APK to the device in the background and completes the installation automatically, unnoticed. This technique is employed to evade detection. After installation, an intent is sent to signal that the package has been successfully installed.

Sharpening targets

In the latest iteration of the malware, the scope of targeted entities has been significantly narrowed, with a clear focus on banks and financial institutions. The once-broad range of targets, including cryptocurrency wallets, has been abandoned.

This strategic shift suggests an intention to streamline the attack efforts and concentrate on sectors that manage the most sensitive and valuable data, such as banking credentials and financial transactions. By honing in on these high-stakes targets, the malware becomes even more dangerous, as it now focuses on the most lucrative avenues for cybercriminals.

Who’s behind?

Based on our ongoing analysis of Zanubis, several indicators suggest that the threat actors behind the malware may be operating from Peru. These indicators include, for instance, the consistent use of Latin American Spanish in the code, knowledge of Peruvian banking and government agencies, and telemetry data from our systems and VirusTotal.

The focus on Peruvian entities as targets also strongly indicates that the threat actors behind Zanubis are likely based in Peru. These regional indicators, combined with the malware’s ongoing financial fraud campaigns, point to a well-organized operation focused on exploiting local institutions.

Conclusions

Zanubis has demonstrated a clear evolution, transitioning from a simple banking Trojan to a highly sophisticated and multi-faceted threat. The malware has been continuously refined and enhanced, incorporating new features and capabilities. Its focus remains on high-value targets, particularly banks and financial institutions in Peru, making it a formidable adversary in the region.

Furthermore, the attackers behind Zanubis show no signs of slowing down. They continue to innovate and adjust their tactics, shifting distribution methods to ensure the malware reaches new victims and executes silently. This constant refinement demonstrates that Zanubis is not a transient threat but an ongoing, persistent menace, capable of further mutations to fulfill the financial goals of its developers.

As Zanubis continues to evolve and adapt, it is crucial for users and organizations alike to stay vigilant. The threat landscape is constantly changing, and this malware’s ability to evolve and target new victims makes it an ever-present risk that cannot be ignored.

Indicators of compromise

Zanubis 2025 version

81f91f201d861e4da765bae8e708c0d0

fd43666006938b7c77b990b2b4531b9a

8949f492001bb0ca9212f85953a6dcda

45d07497ac7fe550b8b394978652caa9

03c1e2d713c480ec7dc39f9c4fad39ec

660d4eeb022ee1de93b157e2aa8fe1dc

8820ab362b7bae6610363d6657c9f788

323d97c876f173628442ff4d1aaa8c98

b3f0223e99b7b66a71c2e9b3a0574b12

7ae448b067d652f800b0e36b1edea69f

0a922d6347087f3317900628f191d069

0ac15547240ca763a884e15ad3759cf1

1b9c49e531f2ad7b54d40395252cbc20

216edf4fc0e7a40279e79ff4a5faf4f6

5c11e88d1b68a84675af001fd4360068

628b27234e68d44e01ea7a93a39f2ad3

687fdfa9417cfac88b314deb421cd436

6b0d14fb1ddd04ac26fb201651eb5070

79e96f11974f0cd6f5de0e7c7392b679

84bc219286283ca41b7d229f83fd6fdc

90221365f08640ddcab86a9cd38173ce

90279863b305ef951ab344af5246b766

93553897e9e898c0c1e30838325ecfbd

940f3a03661682097a4e7a7990490f61

97003f4dcf81273ae882b6cd1f2839ef

a28d13c6661ca852893b5f2e6a068b55

b33f1a3c8e245f4ffc269e22919d5f76

bcbfec6f1da388ca05ec3be2349f47c7

e9b0bae8a8724a78d57bec24796320c0

fa2b090426691e08b18917d3bbaf87ce

Zanubis in motion: Tracing the active evolution of the Android banking malware